Halfway through the first episode of the second season of Breaking Bad, crystal meth cook Jesse Pinkman suggests Walter White, his former chemistry-teacher-(then-barely-)turned-meth-kingpin, that they kill psychotic Mexican drug honcho Tuco Salamanca using two guns and five bullets. “I’ve got a better idea,” says Walter. “Beans. Castor beans.”

“So, what are we gonna do with them?” reacts Jesse, confused and curious. “Are we just gonna grow a magic beanstalk, huh? Climb it and escape?” “No, we are going to process them into ricin,” says Walter. “It’s an extremely effective poison. It’s toxic in small doses. Back in the late ’70s, it was used to assassinate a Bulgarian journalist. The KGB modified the tip of an umbrella to inject a tiny pellet into the man’s leg.”

It might seem like something out of a Batman comic or a James Bond movie, but it really happened: they did, the KGB really did use a ricin pellet and a modified umbrella weapon to kill a Bulgarian dissident in London. No better cue to go back to the boiling mid-days of the Cold War, just between the end of the Vietnam War and the beginning of the Soviet-Afghan conflict, in the dying days of the summer of 1978, the summer of fear…

The murder of Georgi Markov

1. The incident

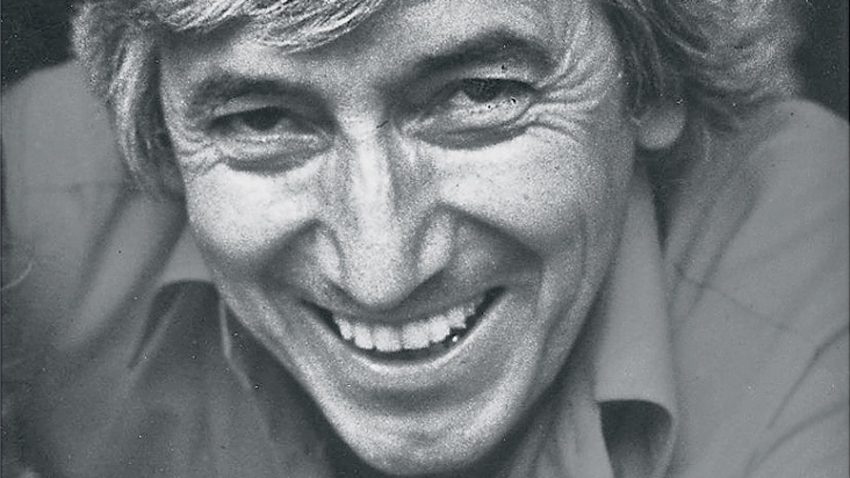

The sun had just begun to rise over London in the early hours of September 7, 1978. In the murky shadows of the dawn, 49-year old Georgi Ivanov Markov, a Bulgarian defector and journalist, was making his way to a now-famous Waterloo Bridge bus stop: just like most of the days for the previous six years, he was trying to catch an early bus to the BBC offices, where he was working as a broadcaster for the Bulgarian section of the BBC World Service.

Little did Markov know, however, that this morning would be anything but ordinary. As he stood waiting for the bus, he suddenly felt a sharp pain, similar to an insect bite, on the back of his right thigh. He quickly looked behind him, expecting to see an insect, but instead he saw a man crouching on the ground, picking up an umbrella. The man looked up, met Markov’s eyes for a brief moment, mumbled “I’m sorry” in a heavy, foreign accent—and then quickly took off, crossing the street and jumping into a taxi which then drove away.

2. Markov’s death

At first, Markov thought nothing of the mysterious man and the incident. But later that day, he noticed a small red bulge at the site of the supposed sting and told a few colleagues about it, sharing his suspicions that he had been poisoned. His colleagues, however, were a bit dismissive of his claims (just as they had been of similar allegations in the past), laughing off what they perceived as an exaggeration of his boastful, larger-than-life personality.

But Markov’s condition got worse, and later that night, he was admitted to St James’ Hospital in Balham, South London, with a raging fever. Even then, the doctors were unconvinced by his story. By the time they realized this wasn’t just another Cold War fantasy, it was too late to do anything—Markov’s metabolism had been thrown out of kilter, his blood pressure had dipped down to almost zero, and his irregular heartbeat couldn’t be stabilized.

On September 11th, just four days after being admitted to the hospital, Georgi Ivanov Markov passed away, leaving behind a wife, a 2-year-old daughter—and a baffling mystery.

3. The investigation

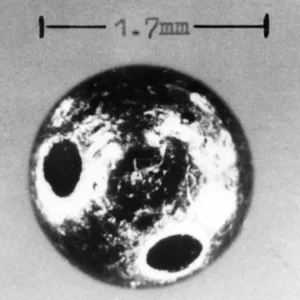

Owing to Markov’s status as a communist dissident, and especially due to the outrageous story he had shared with his colleagues and doctors on the day of the incident, the Metropolitan Police ordered a thorough autopsy of his body. To everyone’s surprise, they discovered a tiny pellet, no bigger than a grain of rice, lodged in the back of Markov’s right thigh. Even though the pellet contained no poison at the time of the examination, it did incorporate one interesting feature: two tiny holes drilled at a right angle, so as to form an X-shaped cavity inside it.

Subsequent examination revealed that the cavity must have been originally filled with a minuscule—but nevertheless lethal—dose of ricin, and then covered with a thin layer of some sugary or waxy substance designed to melt at the temperature of the human body. It was the melting of said substance that eventually triggered the release of ricin into Markov’s bloodstream. What triggered the pellet itself, however, was something even more sinister, something out of a spy novel, something ominously remembered today under the name “Bulgarian umbrella”: a pneumatic mechanism hidden inside a normal, regular parasol.

The umbrella gun: history and design

According to Chuck Willis’ Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weaponry (p. 86), the origins of the Bulgarian umbrella gun—arguably, alongside CIA’s heart attack gun, the most iconic Cold War weapon—can be traced back to “the cane gun” and the beginning of the 19th century. By then, both canes and walking sticks with hidden daggers inside them had already become quite a common sight among the rich elites of Great Britain and the United States. However, it was the introduction of the percussion-cap firing system in the 1810s and 1820s that made a “cane gun” a feasible and tangible option.

The percussion cap firing system was the brainchild of two inventors, Scottish minister Alexander John Forsyth, and English-born American artist Joshua Shaw. Using their findings, at the end of 1823, British gunsmith John Day patented a mechanism wherein a trigger was released when a hammer concealed in a cane was pulled downwards. This became known as “Day’s Patent,” and it became the industry’s standard. Soon enough, the cane gun—marketed as a self-defense weapon—became all the rage, especially amongst naturalists, gamekeepers, and poachers.

Even though it’s not known who built it—or even when it was actually built—it’s safe to suppose that it didn’t take too long after the cane gun for the first umbrella gun to be constructed. The earliest extant example—claims a 2017 article—may be one in the private collection of disguised weapons owned by American David H. Fink, dated 1860. In an enjoyable 1987 article, Fink calls the weapon “a classic example of a British gentleman’s bumbershoot” and describes it thus:

The fine black umbrella is marked “Armstrong reg. British Make” and “Best London Maker.” The shaft of the umbrella is a blued steel underhammer percussion rifle. The bore is .36 caliber. The ramrod fits into the barrel with the point serving to disguise and protect the end of the bore from damage and fouling. The handle is marked “Richard Grinell 1860.” I suspect that Grinell was the owner of this piece, rather than the maker, as I have not been able to find any evidence of a gun maker by this name in this period.

The umbrella gun in pop culture

According to Fink, the design of his “Grinell umbrella gun” is somewhat unusual, as “it uses the entire shaft of the umbrella as a barrel,” as opposed to most other examples of umbrella guns in which “a small pepperbox revolver is concealed in the handle and withdrawn from the shaft for use.” That makes the Grinell umbrella gun even more interesting, as it’s probably quite similar to the one that killed Georgi Markov. We don’t know precisely what it looked like, but Keith Melton, a specialist in espionage tradecraft, holds a Soviet copy of the same design that he believes was used in the assassination. Here he is, talking about it:

In 2003, in the very first episode of MythBusters, Jamie Hyneman and Adam Savage managed to successfully replicate a Grinell umbrella gun, thereby confirming that an assassin can use such a weapon to fire a poison pellet and lethally wound another person. But then again, the Penguin, that supervillanious “Gentleman of Crime,” knew that ever since his first appearance in the early days of the Second World War, famously claiming in Detective Comics #59 (January 1942) that “loading one’s umbrella handle with lead makes things—ah—simpler!”

Almost certainly, that’s what the guys at Marvel’s Kingsman agency believe, as they often tend to use a very special, multifunctional umbrella gun which, in addition to being able to shoot bullets and stun projectiles, can also be used as a ballistic shield. As unreal as the Kingsman umbrella might sound, James “the Hacksmith” Hobson managed to build one—or at least some version of it—in 2017, as part of his “Make It Real” YouTube series. It’s not something anyone else should try to build themselves at home—not even for a kick, not even as a Walter White homage—as they are illegal in most of the world. Also, as the case of Georgi Markov reveals, they are very, extremely, KGB-level dangerous.