For centuries, Europeans participated in a celebratory Dance of The Dead, and the Maître D’ was Death himself.

During ‘The Danse Macabre,’ Death would invite society representatives to dance alongside him en route to the cemetery. Usually, a Pope, a King, a child, a laborer, and a hermit featured most prominently in this procession, organized in order of importance. Other ‘living’ participants followed behind them, all bound for the same destination – The grave.

Those who played the role of Death were cloaked in Skeletal-patterned clothing and a Skeletal mask or headdress. The tradition is believed to be the precursor to the Halloween tradition of costume dress, celebration of the dead, and all things spooky on Allhallowtide (Halloween).

A brief history of the Danse Macabre

Dating back to the Late Middles Ages, The Danse Macabre, also known as the Dance of Death, was an annual procession whereby Death calls upon those from all walks of life to accompany him in a funerary dance to the grave.

The Danse Macabre disrupted the peace of the cemetery and reminded us that no matter who you are or what you have achieved, we are all bound for the ground.

Read more: The Call of the Void and its Perilous Lure

Death is the great equalizer, and so is dancing. Naturally, the two would go hand in hand. No one knew this better than people living in the Late Middle Ages, when you were lucky to live beyond 50.

The Late Middle Ages was a challenging time of great upheaval. The Black Death (1346-1453) wiped out half of the European population already weakened by the Great Famine (1315-1317). The continent enjoyed a brief period of respite before the 100 Years War (1337–1453) between England and France, leaving thousands more dead in its wake.

Not only was death an everyday occurrence for medieval Europeans, but all the drama was also played out amidst the backdrop of socio-religious upheaval between the French state and the Catholic Church.

Incidences of the white skeletons of ‘The Danse’ began to spread throughout the 1500 and 1600s, evidenced by an increasing number of paintings, murals, frescos, and drawings dating back to those periods.

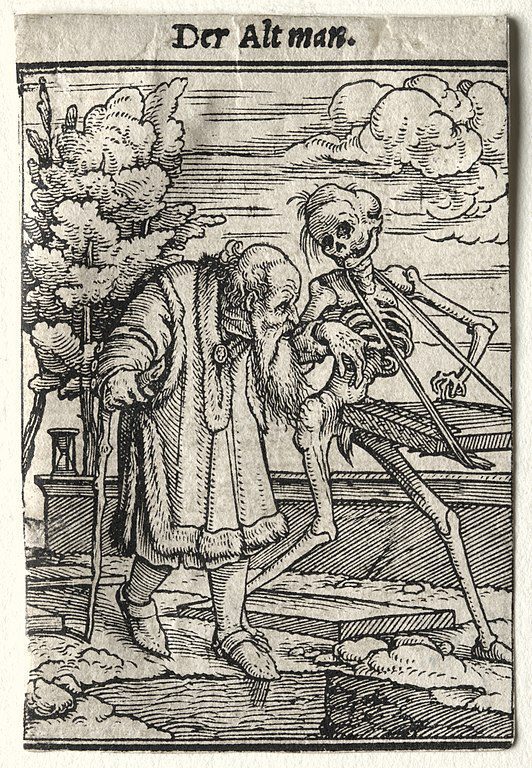

In 1523-26 artist Hans Holbein created a series of Danse Macabre-inspired drawings that depicted people from all levels of society being harassed by a dancing skeletal figure as they go about their daily life.

According to Hans Holbein, Death doesn’t just dance with his victims but also challenges the status quo. Death appears to a judge and snaps his staff in half (the staff symbolizes power). He takes revenge on corrupt politicians and comes to the aid of the peasant by releasing them from a life of toil. Death is both a punishment and redemption; the ‘Danse’ and Holbeins’ drawings are a reminder that he can strike at any moment and are meant as both a comfort and a warning.

Origins of ‘The Danse’

Although The Danse Macabre sounds more like a pagan voodoo legend than a Christian ceremony (more on that later), its roots extend deep into Christian thought.

‘The Danse’ may originate as far back as early medieval drama and music, where figures dressed as skeletons accompany characters to their deaths and engage in a final dialogue. Additionally, a liturgical sermon in Normandy dating back to 1393 featured illustrations of what can only be recognized as The Danse Macabre.

However, the earliest depiction of ‘The Danse’ was found in France, dating back to around 1424. Images of The Danse Macabre were found on a mural in the cemetery of the Holy Innocents in Paris. The mural features various figures engaged in a deathly dance with corpses on their way to heaven or hell. Similar paintings, mosaics, and frescos have been found in Switzerland, Germany, and England; all appear to be based on the mural at Holy Innocents.

The Danse Macabre in popular culture

However, the most popular and notable awareness of The Danse Macabre took place during the 19th Century, when French composer Camille Saint-Saëns brought ‘The Danse’ to the masses when he wrote a musical piece by the same name.

Camille Saint Saëns’ Danse Macabre was based on an old French legend that Death comes to play the fiddle at midnight on Halloween. Originally published as an art song by Henri Cazalis, the tone poem had lyrics with lines such as ‘the bones of the dancers are heard to crack,’ but in Saint Saëns’ version, the lyrics were replaced by solo violin, simulating the sound of the rattling of bones.

A haunting Georgian chant known as Dies Irae is introduced halfway through the piece, adding to the chilling atmosphere. Despite receiving much criticism at the time for its anxiety-inducing undertones, the poem is now a timeless orchestral piece that sits as one of the most famous ‘Haunting’ tunes of all time.

It is most famously featured in Walt Disney’s 1929 Skeleton Dance and has since been the theme music for the BBC television series Jonathan Creek. It is an epic tune for figure skating, Jameson Irish Whiskey commercials, features at the end of Shrek the Third, and hundreds of ballet performances.

The ‘Danse’ today

Although Death no longer dances across Europe, the tradition can still be found in Catalonia. ‘Procesión de Verges con la Danza de la Muerte’ or ‘Verges Dance of Death‘ is a version of the dance that is still alive and well.

It is performed every night on Easter Thursday, only in Verges in Catalonia, after the traditional Christian daytime celebrations.

Verges represents a distinct cultural crossover between the Spanish and French. The dance of Death is considered as much a Christian celebration as the ‘Passion of Christ’ processions during Lent.

The African connection

The idea that Death is a shady-skeletal figure that dances the night away and terrorizes the local populace appears to have also found its way into Haitian Voudou. Bawon Samedi (Baron Saturday) is the Haitian God of Death who often appears as a black man wearing a top and tails, white skeletal face paint, or a mask.

Read more: The Aztec Death Whistle and Its Bloodcurdling Scream

Haitian Voudou, and Bawon Samedi, arose from the Christianization of African slaves during the 16th and 17th centuries. Most of the Haitian slaves were either owned by French masters or passed through France, during a time when The Danse Macabre was still alive and well.

The Baron, believed to be the gatekeeper between life and death, was a lover of parties (particularly drinking) and accompanied the dead to the afterlife. Although Bawon Samedi was certainly a mischievous spirit, he was either malevolent or benevolent, depending on who was telling the story. The Baron toys with his victims, reminding them that no matter what happens in the mortal realm, they must one day succumb to him.

A coping mechanism for death

The Danse Macabre was a popular European festival that sprung from a mixture of Christian ideals and societal anxiety about death. Death was a frequent bedfellow for our Late Middle Ages ancestors, and the Dance of Death was an acknowledgment of the role of death throughout life.

‘The Danse’ was an annual reminder that our worldly existence will ultimately come to an end, regardless of our status or position.

To most during this time, death was a relief—a welcome friend that delivered the poor from poverty, sickness, and suffering. To the rich and the powerful, the end of life was a different matter entirely. Death was a loss to them, and dancing with death reminded them to be more giving, more grateful, and more repentant of their sins.

Although ‘The Danse’ still exists, the iconography of the skeletal-faced Lord of Dance has transmuted. Wrote into history and popular culture, ‘The Danse Macabre’ is now the ghostly inspiration for haunting tone poems, Halloween themed music, scary costumes, Allhallowed house parties, and ghastly figures of legend.