George Everest was a British surveyor and geographer who was posted to India as Surveyor-General from 1830 until 1843. As you might’ve expected, he is most famous for having the highest mountain in the world, Mount Everest, named after him by the Royal Geographical Society, despite the fact he never really had anything to do with the discovery.

Straddling the modern-day border between Nepal and China, Mount Everest, the world’s highest mountain, is an interesting place for Sir George’s surname to be found, on the illustrious old peak XV.

Education and Early Life of Sir George Everest

On July 4, 1790, Everest was born as the eldest son (but third child) of Lucetta Mary and William Tristam Everest. Everest was given a military education at the Royal Military College in Marlow, Buckinghamshire. He distinguished himself in his engineering training before joining the East India Company in 1806. Everest left for India within the year, spending most of the next seven years as a Second Lieutenant in the Bengal Artillery.

The Move Across the World

Everest’s first years in India are a mystery. We know he was taken to Java in 1814, appointed to survey the island, and had returned to Bengal by 1816 – where he was tasked with developing British geographical knowledge of the area around the Ganges and Hooghly.

This was an enormous task for a young man, relatively new to the subcontinent, marking an essential step in the survey of India. Everest was required to use primitive theodolites, a precision instrument for measuring angles, but one that, in reality, could not take an accurate measurement. He was assigned to continue measuring the meridian arc from the subcontinent’s southern tip with inadequate surveying equipment.

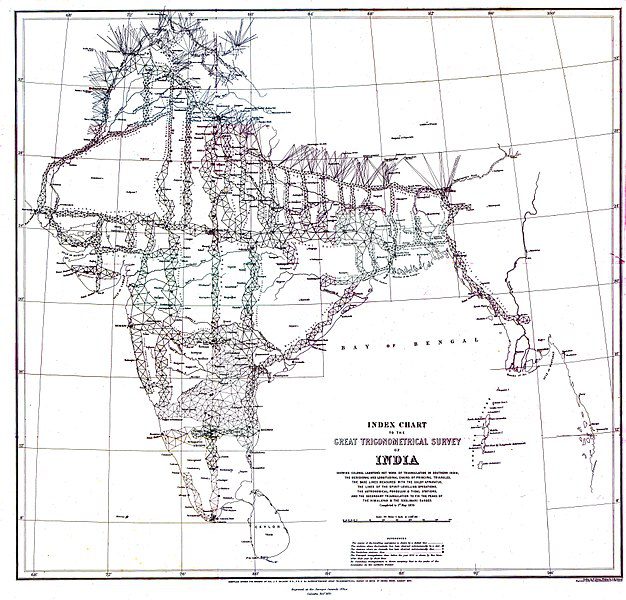

George Everest made his name, attracting the attention of Colonel William Lambton, who led the Great Trigonometric Survey across the entire Indian subcontinent. The survey continued across most of Everest’s life, mainly while he was on the Indian subcontinent. Then after Lambton died, the survey of India was to become his life’s work.

Sir George Everest took the role of superintendent of the GTS in 1823, after Lambton’s death in 1825. Despite suffering from poor health and partial paralysis from fever and rheumatism. Everest’s poor health allowed him to lead the Great Trigonometrical Survey for two years, after which he left for Britain, spending the rest of the 1820s recuperating. Though it wasn’t all bad for Everest, he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in March of 1827. He brought home important calculations for the Great Arc, which was poured over by the engineering and scientific community.

The Return to the Subcontinent

Sir George Everest returned to India to pick up where he left off with the Great Trigonometric Survey and was appointed the Surveyor General of India. During this time, the arc from Cape Comorin (Kanyakumari – the southernmost point of the Indian subcontinent) to the northern border of British India continued to be mapped, being completed under his deputy and protege Andrew Scott Waugh in 1841.

Administrative Issues

Everest didn’t have the opportunity to enjoy his work mapping India with the Great Trigonometrical Survey. He was plagued by administrative issues, resulting in significant criticism from back home. Thomas Jervis was George Everest’s intended successor as surveyor general for the East India Company, delivering a series of lectures on how ineffective Everest and his team’s methods were on the survey of the subcontinent. Everest penned a series of letters to the Duke of Sussex, president of the Royal Society, arguing that the society shouldn’t meddle in matters that they did not understand.

After this, Jervis withdrew, leaving Scott Waugh the natural choice to be Everest’s successor. Finally, Sir George Everest retired in 1842, with his commission revoked in December of 1843 – as he returned to England once more.

Later Life

Everest continued into his later life, taking on new expeditions, such as being a passenger on the first voyage of the SS Great Britain, which was the first screw-propelled steamship to cross any ocean. He also published several works, not least An Account of the Measurement of Two Sections of the Meridional Arc of India, in 1847 – being awarded a medal by the Royal Astronomical Society.

A Hero’s Return

Everest was bombarded with many different awards and ceremonial promotions. After being promoted to colonel in 1854, George Everest was then made a commander of the Order of the Bath in the February of 1861 and summarily honored as Sir George Everest in March of the same year, as Knight Bachelor.

Read more: Kailasa Temple: Massive 8th Century Temple Built Top-Down

Sir George Everest, the man who quite literally defined India, died on December 1, 1866. He was buried in St. Andrew’s Church, Hove, England.

Everest and Andrew Scott Waugh

By hiring Andrew Scott Waugh, Everest made perhaps his most outstanding contribution to the world in having Mount Everest named after him. The new Surveyor General of India asked the Royal Geographical Society in March of 1856 to name the mountain after his predecessor. Still, for a decade after Waugh’s initial suggestion, the society continued to debate.

It’s the Name of the Game

Most debates surrounded issues about the native naming rights to the mountain. Local names from Tibetian and Nepalese porters were preferred for the mountain, being referred to as “Deva-dhunga.” The mountain was also called “Chomolungma” by local Tibetan and Nepalese porters, translating to ‘Goddess Mother of the World’ in the local Tibetian dialect. To compound this, George Everest wasn’t in favor of his name being used because natives of India may struggle to pronounce it and had no direct Hindi translation!

The mountain was first spotted from a location above the hill resort of Darjeeling. After the world’s highest peak was measured via theodolite, it was initially named ‘Gamma.’ However, this was later changed to ‘Peak B’ in 1847, and then ‘Peak XV.’

The Royal Geographical Society remained cautious. They wanted the mountain named something pronounceable by locals and did not want to impose British names merely due to the trigonometrical survey that helped map it.

Needless to say, and as we all know, the society settled on Mount Everest as the name of the peak, due to the ‘native appellation’ being too difficult to ascertain without much further research into the Himalayas and more surveying of Nepalese mountains and culture.

The Legacy of Mount Everest

Mount Everest has been consistently the crown jewel of modern-day mountaineering. There is no shortage of interesting facts coming from the world’s highest peak in Nepal.

There is still uncertainty surrounding who truly conquered the highest mountain in the world – and whether George Mallory and Andrew Irvine first scaled it. Officially, the highest peak remained unconquered until the 1950s, with Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s ascent on May 29, 1953. The mountain remains today, the highest in the world, something we can tell thanks to satellites rather than surveying – but not without thanks to Sir George Everest and, of course, his trusty companion Andrew Scott Waugh.