The Habsburg jaw quickly became one of the most striking images of early modern Europe, as the royal family tree quickly became littered with examples of a very defined jawline. Experts have since suggested that the distinctive Habsburg jaw developed due to the incestuous relationships that permeated the Habsburgs.

But who were the Habsburgs? Where did they originate? Who are the notable names and figures? Where did their jaw develop? How did we find that the European royals caused the Habsburg jaw to exist by inbreeding?

A study from the University of Santiago de Compostela may hold the answers.

The origin of the Habsburg dynasty

The Habsburg dynasty, and the jaw that came alongside it, originated in Switzerland, where Radbot of Klettgau named his fortress Habsburg in the 1020s. Soon, the title ‘Count of Habsburg’ was commonly used. From this derived the use of the title as the last name.

From here, the Swiss Habsburgs soon became the Austrian family we know of today—as Rudolph of Habsburg was elected as Holy Roman Emperor and subsequently moved the family’s power base to Vienna.

Charles V (or as he was on the other side of the continent, Charles I of Spain) was the Archduke of Austria, King of Spain (the united Castile and Aragon), Lord of the Netherlands, Duke of Burgundy, and also, Holy Roman Emperor.

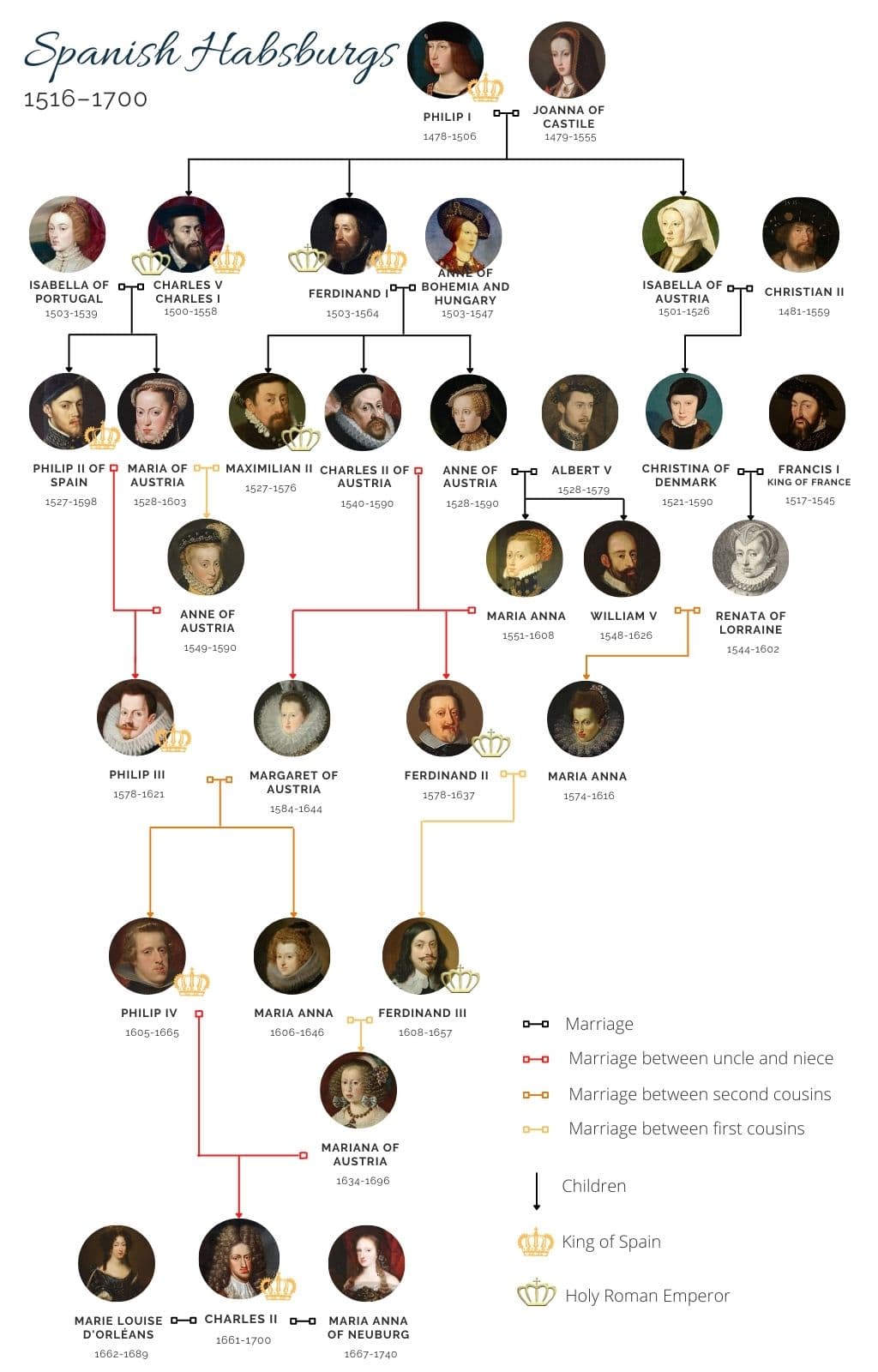

From Charles came the line of Spanish Habsburgs, as he was the last of the united line to have ruled Spain, splitting his inheritance between his brother and son in 1556, creating an Austrian and Spanish line of the Habsburg Family. From here, it was easy for the two families to continue their alignment through the 16th century and the Thirty Years’ War—through tactical royal marriages.

However, the royals remain today, in the form of Karl von Habsburg—a modern example who does not have any birth defects, or at least any disclosed to the general public. Karl represented Austria, in the 1990s, as a member of the European Parliament, a role which, when taken up, required his family to renounce any claim to the now-defunct thrones of Austria and Hungary.

The royal family tree

The Habsburg jaw has been subject to many studies, including that published in the Annals of Human Biology, which found that, unsurprisingly, the facial deformity most likely originated from inbreeding. Where did this inbreeding begin, and where did the Habsburg jaw originate?

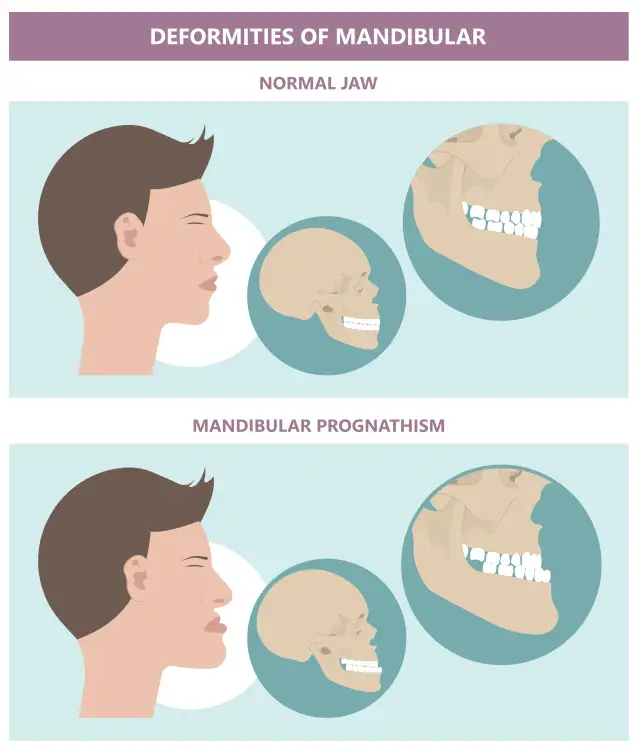

From his abdication in 1556, the Spanish monarchy was descended from Charles V, through to his son, Philip II, and so onward. It is suggested that Philip IV, Charles V, and Charles II of Spain all possessed facial deformities typical of mandibular prognathism, otherwise known as MP, or protruding jaw, alongside maxillary deficiency, the upper jaw lacking development.

The offspring from Charles V had interwed, as a result of two separate royal families, and their dominance over the Pope, who determined whether the marriage was valid in the eyes of the church—resulting in the protrusion. Though it must be said, maxillary deficiency was common in the dynasty before this, with the Habsburg jaw widely reported on by envoys from Maximilian I’s court.

Most interestingly, court painters were required to paint the monarch in ‘their best light,’ and in particular, Charles V and Charles II were both fastidious in matters of art. Perhaps both saw the facial feature as an integral part of their image or as having been reduced significantly by the artist to look good, retaining resemblance.

We can probably speculate that the European royals’ case of the Habsburg jaw was far more significant than previously thought!

Charles II of Spain

Charles II does not refer to Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire, who had many different titles. Instead, we refer to Charles II of Spain, or Carlos II, the man best known for the physical deformities brought on by the Habsburgs’ inbreeding. In this way, the Habsburg dynasty serves as a valuable resource for researchers – as it is well documented that the family’s offspring inheriting identical forms was down to some form of inbreeding.

Charles II of Spain was the son of his uncle and his uncle’s niece, Philip IV, his father, and his mother, Maria Anna of Austria. The family’s inbreeding was intentional, designed to keep out undesirable claimants to the throne.

There were consequences for the inbreeding in the Habsburg family. When Charles died in 1700, a lack of claimants to the throne led to the War of the Spanish Succession.

King Charles II was, as historical figures go, an undesirable monarch, with his unusual defects baffling contemporaries as to how he continued to live. The French ambassador to Spain suggested that ‘the Catholic King is so ugly as to cause fear, he looks ill,’ meaning that the Spanish throne was never secure until Charles’ passing.

Reports even circulated around the European royal family that Charles did not chew his food thoroughly enough due to his prominent facial deformity and was prone to choking on his food! Alexander Stanhope reported that Charles II had a ‘ravenous stomach,’ and that his ‘nether jaw stands out,’ meaning that his teeth were unable to meet. By the end of his reign, he was nicknamed El Hechizado, meaning ‘the hexed one’—such was Carlos’ struggles with his facial deformities and other litanies of health issues that plagued his reign.

Research on the Habsburg jaw

The Habsburg jaw itself has been studied significantly to identify key features between family members. Researchers have tried to determine whether it was a matter of bad luck, or, as suggested for generations, a case of inbreeding and genetics that gave the Habsburgs, particularly the Spanish Habsburg kings, their prominent lower lip. Investigators were keen to point out that inbreeding is still commonplace today, in different geographical regions and among some religious and ethnic groups—not merely monarchs of the most famous European royal families.

The Habsburg jaw, and the overall effect of the incestuous methods of the family tree can be explained via an inbreeding coefficient, developed by the study led by Román Vilas, of the University of Santiago de Compostela. Vilas suggested that the “Habsburg dynasty serves as a human laboratory for researchers.” Researchers detected a strong relationship between the degree of mandibular prognathism and the level of inbreeding within the family.

For example, the inbreeding coefficient of the child of two first cousins would’ve been .0625—meaning 6.25% of the time, this child would have around that percentage of corresponding genes that were identical. The Habsburg dynasty’s royal inbreeding resulted in a .093 coefficient. 9.3% of the time.

A Habsburg had genetic homozygosity—the aforementioned identical forms of genes. A difference of roughly 3% does not immediately strike you as being statistically significant, but compared to the usual risk of humans having deformities resulting from breeding with an unrelated partner, a 3% difference is enormous.

The famous Habsburg jaw, prominently featured by Charles VI, Charles II, and Philip IV of Spain – probably had a far more significant inbreeding coefficient. The coefficient, in this case, was estimated to stand at around 22% for the degree of mandibular prognathism – meaning as marriages went on, such as from Maximilian I onward to the man who caused the eventual downfall of the dynasty in Spain, Charles II – the problem would only get worse!

Which Habsburgs were studied

The study focused on several different family members of, predominantly, the Spanish Habsburgs. The greatest degree of maxillary deficiency was identified in five members of the family: Maximilian I of the Holy Roman Empire; his daughter, Margaret of Austria; Maximilian’s nephew; Charles I of Spain, Charles I’s great-grandson; Philip IV of Spain and, of course, his son; Charles II. Unsurprisingly, the lowest measure of inbreeding coefficient was detected in Mary of Burgundy—who married into the family!

Seven features were identified, though only two were diagnosed as being resultant from genetic homozygosity. Of these two, the Habsburg jaw was one. Research showed that the lower part of the human face was the most sensitive to inbreeding. This is a recessive trait, which meant that its continued participation in the Habsburg line was a result of continued intermarriage. Even interspersed with the occasional outsider marriage—this gene would be present.

Of course, biological material was unavailable for the study, so researchers used portraits, many of which were located in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Each of the portraits used had confirmation that the royal it portrayed had seen it when alive and had given their blessing to ensure the facial feature was not exaggerated without their knowledge.