In the waning years of the 19th century, the Chinese city of Canton (today’s Guangzhou) was “a colossal human anthill, an endless labyrinth of streets a dozen feet wide and a score high, crowded from daylight to dark with a double stream of men and women.” It was here, in the midst of this chaotic street scene, that an inquisitive Briton stumbled upon a sight he would never forget. The photograph he took of the event changed the Western perception of China—forever.

Lingchi through the lens

One fine day in 1890, as he was chugging along the waterway that flowed between Hongkong and Canton, an unidentified British captain of a river steamer was struck with an impulse to explore the city of his final destination. Armed with a newly acquired hand-camera—a luxury only a selected few could afford at the time—he set out on foot, eager to capture the sights and sounds of this bustling locale.

As he wandered through the winding streets of Canton, he noticed a commotion up ahead and pushed his way through the gathering crowd. What he saw next shook him to his very core: there, in the middle of the throng, in the heart of the market place of Matou, lay the mangled remnants of a man who had met his untimely end in the cruelest of fashions, his head and his limbs completely severed from his body, his blood spattered across the street, his lifeless eyes staring blankly unto themselves—and into the godless abyss.

The sight was so gruesome that the British captain felt his stomach lurch and his knees weaken. This was, he realized, the capital punishment of lingchi, a horrendous Chinese form of execution he had only heard of but almost no foreigner had ever seen carried out. Without much hesitation, he lifted his small camera and discretely pointed it in the direction of the macabre spectacle. Quickly snapping the shutter, he captured the moment without drawing any undue attention from the crowd, for they would have probably stopped him had it happened otherwise.

Upon his return to Hongkong, the captain turned to an experienced photographer to develop the negative and create an enlargement of the photo. The result was a hauntingly grim image that captured not only the horror of this particular execution but also—soon after—the collectively repulsed imagination of the entire Western world. Indeed, when the photograph first appeared in print, in Sir Henry Norman’s 1895 broadly read travelogue, The Peoples and Politics of the Far East, the relevant page was graciously perforated “in order that it may be detached, without mutilating the volume, by any reader who prefers not to retain permanently so unpleasant an illustration of the condition of contemporary China.”

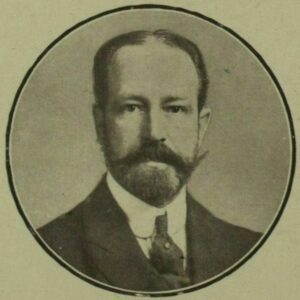

Sir Henry Norman in the shambles

Sir Henry Norman, an English journalist and politician, was a privately educated and widely traveled writer. He had the rare opportunity—and the sufficient funds—to visit China on numerous occasions in the late 19th century and witness firsthand some of the seemingly barbaric practices of the Qing dynasty. “Nobody can claim to have an adequate and accurate appreciation of the Chinese character who has not witnessed a Chinese execution,” he reported back to the West in 1895. “I have looked upon men being cruelly tortured; I have stood in the shambles where human beings are slaughtered like pigs; my boots have dripped with the blood of my fellow-creatures.”

It is to Norman that we owe both the publication of the very first photographic rendering of a lingchi execution, and also one of the earliest foreigner’s descriptions of this traditional method of Chinese torture:

The criminal is fastened to a rough cross, and the executioner, armed with a sharp knife, begins by grasping handfuls from the fleshy parts of the body, such as the thighs and the breasts, and slicing them off. After this, he removes the joints and the excrescences of the body one by one—the nose and ears, fingers and toes. Then the limbs are cut off piecemeal at the wrists and the ankles, the elbows and knees, the shoulders and hips. Finally, the victim is stabbed to the heart and his head cut off. Of course, unless the process is very rapidly carried out, the man is dead before it is completed, but if he has any friends who are able to bribe the executioner he is either drugged beforehand with opium, or else the stab to the heart is surreptitiously given after the first few strokes.

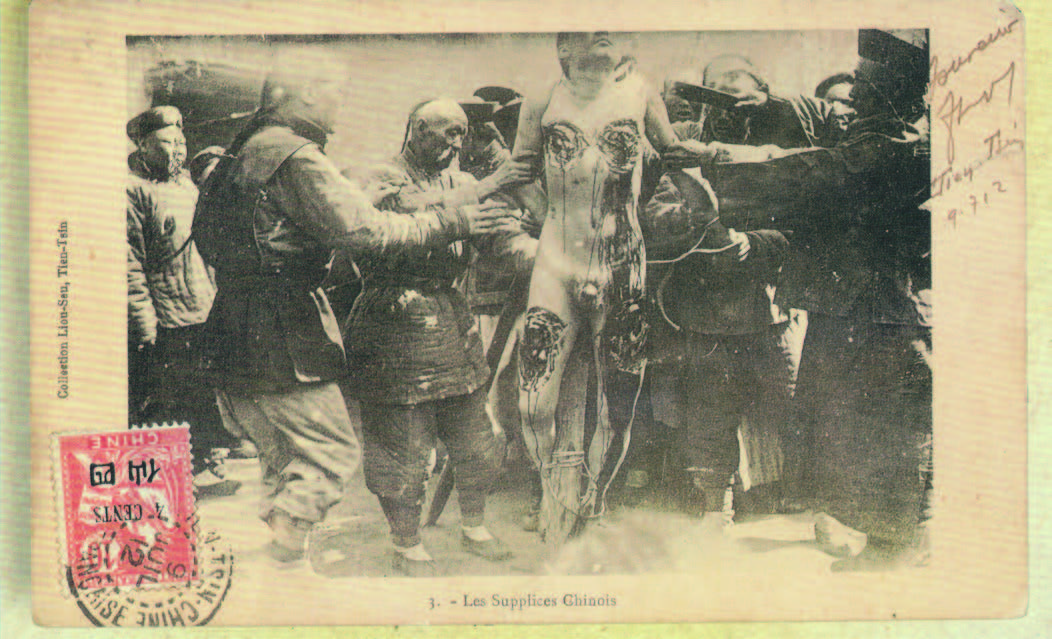

In 1895, Norman could justly claim that a lingchi execution had only once been witnessed by a foreigner; in the decade that followed, that all changed, and changed utterly. Following the Boxer Rebellion—an anti-colonial and anti-Christian uprising in China from 1899-1901—foreign military forces occupied Beijing, allowing Europeans to travel freely around the city. It was during this time that descriptions and photographs of lingchi executions began to circulate among Europeans as curiosities and mementos. These pictures were often collected and shared in Europe, with postcards being a popular format for their dissemination.

The availability of these images reflects the intersection of Western hypocrisy, colonial power, and the growing fascination with exotic cultures that characterized the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Europe. It also reflects a few things far more sinister—the furtive fetishization of violence, the morbid curiosity toward the suffering of others, and the dehumanizing objectification of non-Western peoples by Westerners, who viewed them then (and sometimes view them still) as barbaric and uncivilized, fit only for subjugation and domination. The truth, as always, is far more complex.

Slow slicing the system: lingchi and Chinese law

The macabre spectacle of a lingchi execution, once confined to the streets of China, was catapulted to the global stage through the power of early 20th-century photography. As European visitors to China (most commonly French soldiers) captured and circulated images of these tormented killings, they became more than mere curiosities—they became potent symbols of Chinese inhumanity and savagery. According to historians Timothy Brook, Gregory Blue, and Jérôme Bourgon—writing in Death by a Thousand Cuts, the authoritative work on the subject—these photographs transformed lingchi into a cultural icon, perpetuating a narrative of Chinese otherness and exoticism that reverberated far beyond the realm of law and into every aspect of Western perceptions of Chinese culture.

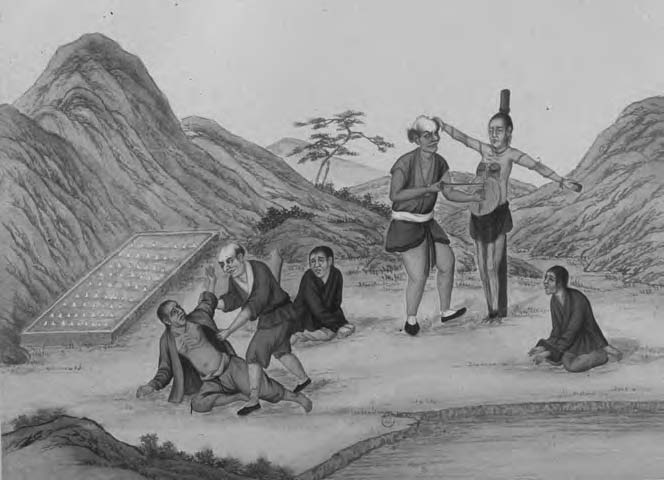

Legally, however, lingchi was not some peculiar cultural aberration, but an extreme form of the death penalty in premodern China, grisly beyond belief, but not particularly grislier than familiar European practices such as the Roman fustuarium, the Spanish Inquisition’s autos-da-fé or American racial lynch mobs. Much like the early modern English practice of hanging, drawing and quartering, lingchi involved “the methodical slitting and cutting apart of the body of the condemned in a stipulated number of cuts performed in a prescribed sequence.” Predictably, “the cutting began before the convict was dead, proceeded according to prescribed numbers, and continued well beyond the point of death until the body was fully dismembered.”

No such punishment—or anything resembling it—is mentioned in the Tang Dynasty Code of 653, the earliest fully surviving legal code from China, which set the standard for many subsequent legal codes in the country and elsewhere in East Asia. Dismemberment (in any form or sort) first became part of the Chinese penal system about four centuries later, when the Liao and Song dynasties introduced it as a punishment for high treason, mass murder, and rebellion. However, it was during the Yuan dynasty of the Mongols that lingchi chusi—or “putting one to death by lingchi“—was first formally acknowledged in the Chinese penal code, becoming a commonly used form of execution only later, during the Ming (1368—1644) and Qing dynasties (1636—1912).

Cutting through the linguistic layers

In modern Chinese, lingchi doesn’t mean anything—or at least not something particularly obvious. As Brook, Blue, and Bourgon explain, the word is usually read as a composite of two seemingly incongruous Chinese characters: ling, meaning “ice,” and chi, meaning “delay” or “lateness.” This is where the common translations of lingchi as the “slow process” or “lingering death” come from, indicating “death that comes on as slowly as ice forms.”

However, in Classical Chinese, ling doesn’t mean “ice” but “hillock” or “(burial) mound.” Indeed, the earliest mention of the word lingchi (in a philosophical parable written by the fourth-century B.C. Confucian philosopher Xun Kuang) describes the relative ease of traveling in a horse-drawn carriage through mountainous terrains (as compared to doing the same over a wall) because of the “slow/gentle ascent/descent.” This is precisely how the term lingchi was translated all the way until the 10th century, most commonly being used as a metaphor for “the gradual decay of an institution.”

It was only after China fell under the rule of Inner Asian dynasties (the Khitan Liao, the Jurchen Jin, and the Mongol Yuan) that ling came to mean “ice” and lingchi acquired the meaning of “slow and lingering death” (or “slow slicing”). According to late Qing Dynasty reformist Shen Jiaben—the man who legislated the abolition of lingchi during a major intellectual and government reform in 1905—the semantic shift occurred not only through linguistic confusion, but by way of an inherent analogy. In his own words:

The meaning of lingchi is that the hill rises gradually, just as, when killing a man, the wish is that his death be slow and gradual. This is how the language of ‘step by step’ or ‘gradual’ was transferred to the term for gradual execution.

The clandestine cruelty of a merciful mutilation

Five years after Sir Henry Norman published The Peoples and Politics of the Far East—wherein he portrayed East Asia as “the last Wonderland of the World”—Algernon Bertram Mitford, a British diplomat in Beijing in the 1860s, published an epistolary account of his own experiences in the region, titled The Attaché at Peking.

Near the end of the 19th letter—via a thinly veiled reference to Norman—he claimed that lingchi executions were actually “conducted far more mercifully than one is led to suppose by certain writers.” Though he admits to have never seen a lingchi execution himself, Mitford also says that a firsthand witness from England assured him “that the criminal he saw so executed was put out of his misery at once, and that the mutilation took place after death and not before.”

While Chinese legal tradition—otherwise quite diligent and comprehensive—features almost no reports of executions (let alone detailed accounts as those in Europe), Mitford’s take seems to reflect contemporary reality much better than Norman’s. In fact, in more ways than one, Norman (and most of the Western world) missed the point of lingchi entirely, in every way from its cultural significance to its legal framework.

Namely, even though it’s undoubtedly true that some of the early executions were intended to inflict utmost pain and humiliation—the lingchi of Yuan Chonghuan, a Ming Dynasty general, lasted for 12 hours, and that of the hated eunuch Liu Jin, the longest one on record, for two whole days!—their purpose seems to have extended beyond mere physical suffering. One might even say that it extended beyond death as well: lingchi, by all accounts, wasn’t really about tormenting the miscreant, or even killing them; rather, it was about preventing them the chance of a proper afterlife.

The real lingering death

Chinese culture attaches great significance to bodily integrity, and its loss carries severe repercussions: for Buddhists, it signals the end of the cycle of rebirth, while for Confucians, it means forfeiting the benefits of sacrificial offerings. Hence, as stated in the Jade Record—an illustrated 19th-century religious tract describing the retributive justice of Chinese afterlife—the most feared punishment of all is total annihilation (“such that not a hair remains”), followed by slow slicing (lingchi) and decapitation, as they all bar the dead from entering purgatory whole and repaying their karmic debt to be reborn.

Put otherwise, the Chinese didn’t fear lingchi “because of any torture associated with its performance, but because of the dismemberment practiced upon the body which was received whole from its parents.” This quote is taken from An Australian in China, another 1895 travelogue about the country written by an English-speaking visitor, this time the London Times correspondent George Ernest Morrison. More perceptive than Norman—and far less prejudiced—Morrison was one of the first non-Asians to realize that a lingchi execution, while ghastly and horrid, was not nearly as cruel as it might have seemed to an uneducated foreigner. Writes he,

The mutilation is done, not before death, but after. The method is simply the following, which I give as I received it first-hand from an eye-witness:—The prisoner is tied to a rude cross: he is invariably deeply under the influence of opium. The executioner, standing before him, with a sharp sword makes two quick incisions above the eyebrows, and draws down the portion of skin over each eye, then he makes two more quick incisions across the breast, and in the next moment he pierces the heart, and death is instantaneous. Then he cuts the body in pieces; and the degradation consists in the fragmentary shape in which the prisoner has to appear in heaven. As a missionary said to me: ‘He can’t lie out that he got there properly when he carries with him such damning evidence to the contrary.’

Beyond the blade: the fight to end lingchi as a capital punishment

“More than any other penalty,” reckon up the authors of Death by a Thousand Cuts, “lingchi violated what one historian of Chinese law has termed ‘somatic integrity’—the capacity of the body to remain whole, in death as well as in life. The loss of somatic integrity was the outcome most feared and the threat most potent in the system of imperial punishments.” As a result, whenever the practice of lingchi was challenged throughout Chinese history, it was challenged on religious, and not on secular, grounds. In other words, over the span of a millennium, lingchi was never condemned as an act of barbaric torment, but an impious practice of desecration, an irreverent breach of the holy cosmic order.

This is precisely how lingchi was contested by Lu You, a 12th-century poet and official, in his Memorial of Itemized Answers. A vocal opponent of the practice in the earliest years of its institutionalization, Lu argued that the ultimate means of punishment should be (as it had been under previous dynasties) decapitation, as lingchi “wounded the harmonious interaction of heaven and earth” and went against the principles of benevolence in governance. “Any penal system must include kindness to work efficiently,” wrote Lu, an opinion echoed by a host of Chinese critics of lingchi, all of whom knew well what Westerners still don’t—that lingchi was always an aberration of Chinese law, and not its epitome.

Lu You’s elaborate argument against lingchi influenced the call for its abolition. “How could something like this be deliberately instituted?” wondered Shen Jiaben, just before penning the final edict against lingchi, which was officially outlawed on April 24, 1905. Four years before that, to the day, an influential landowner by the name of Wang Weiqin descended on the home of a certain Li Jichang, killing him and another 11 members of his family. Shortly after, he was sentenced to death by lingchi for mass murder. Several French soldiers went to witness his execution, in the autumn months of 1904. They took many photographs of the event and sent them back home as postcards—to be picked up by newspapers, and fleshed out into gruesome narratives of Oriental horror by decadent novels and detective stories. On the eve of its abolition, lingchi suddenly became emblematic of a China that never existed, of a barbaric and backward society that was out of step with the modern world.