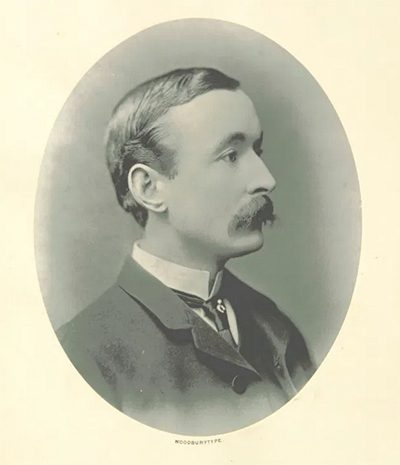

James Jameson was simultaneously an esteemed naturalist of the late 1800s and the spoilt heir of an Irish whiskey magnate. James Jameson would experience a life of travel, exploring the dark reaches of the Congo, an experience of toil, anguish, disease and cannibalism. On Henry Morton Stanley’s expedition, he experienced the glorious highs and cannibalistic lows of late Victorian explorers on the notorious Emin Pasha Expedition.

Who was James Jameson?

James Jameson, grandson, and heir of Jameson Irish whiskey magnate John Jameson typified what it meant to be filthy rich in the 19th century. By 1877, Jameson had decided upon a life of travel, leaving for Ceylon, then onto Singapore, and finally Borneo. Jameson was the first to discover the elusive Black Pern, a honey-buzzard-like creature, collecting other samples of exotic flora and fauna, returning home an accomplished naturalist.

A grand tour of South-East Asia couldn’t satisfy the appetite of the young heir as he sailed off once more on another great adventure. By 1878 Jameson was hunting big game on the outskirts of the Kalahari desert in South Africa, and in 1879, hunting for lions and rhinoceroses up the Limpopo River. The whiskey heir returned triumphantly to his family, flush with the spoils of another successful expedition, while unbeknownst to him, his next trip to the great continent was to be his last.

Shipping up to the Congo!

Jameson shipped out to the Belgian-owned territories of the Congo to take part in the last ‘Great expedition.’ King Leopold II of Belgium owned the region, and unlike his constitutional rule in Belgium, ruled as an absolute ruler. The Congo Free State, which Leopold founded, was helped by the expedition leader, Henry Morton Stanley – to lay claim to the region. Leopold legitimized his conquests through the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, where other European colonial nations authorized his claim.

To get his claim authorized, Leopold claimed to be improving the lives of native inhabitants. He didn’t. Millions of Congolese died at the hand of Leopold’s mercenary Force Publique or succumbed to diseases. Congolese failing to meet rubber collection quotas faced death. Leopold extracted a significant amount of wealth from his private kingdom, collecting ivory initially, then rubber importations from the 1890s onwards. Historical estimates suggest that around 10 million – potentially up to 15 million – died due to Leopold’s regime.

The ‘relief’ mission in Equatoria, ironically, was traveling through one of the most devastated parts of the continent, with no regard for the natives other than the services they could provide.

Read more: The Bob Semple Tank: Worst Tank Ever

The Emin Pasha relief expedition.

The Emin Pasha relief expedition was one of the last European journeys into the interior of the continent, intended to relieve Emin Pasha. Emin Pasha, also known as Eduard Schnitzer, was an Ottoman-German-Jewish physician appointed Governor of the province of Equatoria (modern-day South Sudan) on the upper Nile in 1878. Pasha had been close with his predecessor, Charles George Gordon, who appointed him as chief medical officer of the province – eventually nominating him as his successor. Pasha was vital to regional stability, continuing Gordon’s work in disrupting slavery across the region, something that the British and Ottoman governments were keen to retain.

Emin Pasha had found himself trapped by the revolt of Muhammad Ahmad and his Mahdist followers. Pasha retreated to Wadelai in 1885, 40 miles (64km) north of Lake Albert, and desperately requested European aid. After the attempts of Gordon to alleviate the situation and his year-long defense of Khartoum, public enthusiasm and pressure on the government resulted in the dispatch of a relief force to Equatoria. This Nile expedition came too late for Gordon and his 6,000 men, and Emin Pasha was still in significant danger. By 1887, the de-facto British territory in Egypt and Sudan was at considerable risk, and so a new expedition was undertaken to rescue Pasha. After the death of Gordon, Pasha’s conviction to remain in Equatoria was strong – as was British public sentiment to ‘avenge Gordon’ by rescuing Emin Pasha.

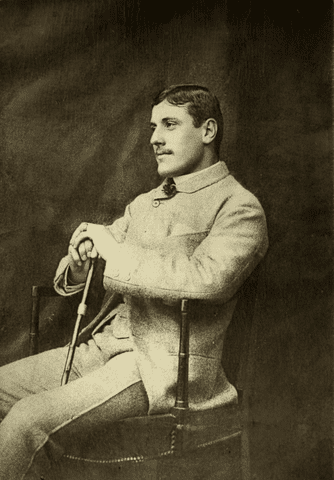

James Jameson’s prowess as a naturalist fought off over 400 other applications to take part alongside Henry Morton Stanley in a great expedition. Of course, his contribution of £1,000 (over £134,000 today) certainly helped his cause. Jameson reached Banana point, a small seaport at the mouth of the Congo in March, and by June 1887, was left as second in command of the infamous rear column. Taking orders from Major Edmund Musgrave Barttelot, his mandate was to remain in an entrenched camp at Yambuya on the Aruwimi tributary, while Stanley’s party pushed onwards in search of Emin Pasha himself. Stanley’s expedition would take him around 500 miles (804km) further into ‘darkest Africa’ – via the dense Ituri Rainforest. Barttelot would become notorious for his maniacal behaviour while in charge of the rear column. He is often attributed to being one of the sources of inspiration for the despotic character of Kurtz in the book Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad.

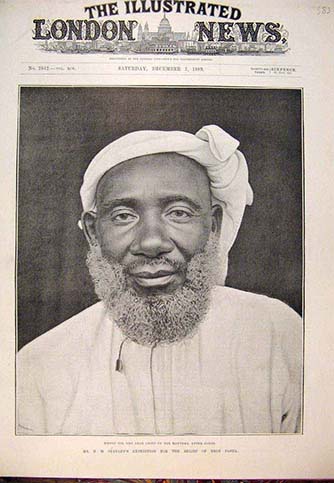

The Zanzibarian trader-ruler of Yambuya, Tippu-Tib, had promised Henry Stanley to send men and carriers the way of the rear-column, after which the reinforced men were to follow through to resupply the main expedition. Tippu-Tib was an Afro-Arab slave trader, ivory trader, and eventual Governor in the region. Tippu had known Stanley from his previous work for Leopold II and his expedition to find David Livingstone after six years in 1871. Tippu had been leading groups of men from his home in Zanzibar into Central Africa to plunder slaves from neighboring provinces and villages from a young age. Allegedly, by 1895, Tippu had amassed over 10,000 slaves to work plantations he had acquired through force.

However, Stanley made a deal with Tippu – which wasn’t taken too well at home – to make him the Stanley Falls District’s Governor. Europe was dismayed by this deal with a slaver, particularly after the heroism of explorers like Livingstone to try and eradicate the practice. In return, Tippu promised provisions and carriers of stores. In the end, Tippu failed to uphold the bargain; hence Jameson visited him at Stanley Falls (modern-day Boyoma Falls) – a 105 mile (170km) journey – without result. A wave of sickness swept through the camp; by 1888, a third of its occupants perished in the heat. Jameson visited Tippu once more, 300 miles (482km) further than their last meeting! The encounter would have a devastating impact on his legacy and overshadow his naturalist accomplishments.

Children eaten by cannibals?

Returning to the settlement of Riba Riba (rebuilt after 1893 as Lokandu) with Tippu, Jameson witnessed native dances and festivities. Tippu

informed Jameson of the great festival at hand in the village and the consumption of human flesh that served as the centerpiece of the banquet. Later testimony from Assad Farran, expedition translator, suggested that Jameson was directly involved in cannibalism. Jameson presented the villagers with six handkerchiefs-a callous provocation to their cannibalistic intent.

The tribesmen looked upon their six handkerchiefs as a challenge, immediately taking a 10-year-old slave girl, killing and dismembering her for consumption. The men allegedly ‘plunged a knife quickly into her breast,’ with the body quickly divided, and with ‘not a particle’ remaining, began to run down to the river to wash their meal.

Assad Farran suggested that Jameson bought the girl himself from the slaver. Farran’s affidavit, published by the New York Times on November 14, 1890, indicated that one of the men challenged by Jameson brought the girl and said, ‘this is a present from a white man who desires to see her eaten.’ Assad suggests that the girl was not fearful and ‘did not scream,’ but looked around her for help, which was not becoming, before her death. The sadistic events would be exposed to the world by 1890, but this wasn’t all.

Jameson was fascinated by the cannibals, writing of his confusion of how accepting the girl was of her fate. As the cannibals ripped into the 10-year-old slave flesh, Jameson, by his own admission in his private writings, ‘could not believe that they were in earnest,’ and yet still tried to ‘make some sketches of the scene.’ Farran’s affidavit claimed that Jameson took six rough sketches ‘in the meantime’ and went back to his tent to finish his illustrations in watercolors! After completion, Farran alleges that Jameson took them to all the chiefs to demonstrate his artistic talent. Unfortunately for him, news of the brutal events had already made it to the Times of London, even before Farran or William Bonny (British army sergeant and doctor member of the rear guard) had the opportunity to give their testimony. Jameson’s inhumanity, his inaction as an innocent child, was eaten by cannibals, and his glorification of barbarous event would never be forgotten.

Final moves and death.

Arriving back at Yambuya on May 31, 1888, Jameson prepared evacuation of the camp, taking place in June. Tippu-Tib, as a slave overlord, eventually provided 400 Manyema to the expedition. The Manyema (Una-Ma-Nyema, eaters of flesh) were a warlike Bantu people, with their capital in Kindu. Many of these men were probably cannibals, based on several sources, including Herbert Ward (who was present on the expedition). Trained from a young age to have loyalty to their master, they had certain expectations. For example, and most notably, Tippu had allowed the Manyema to continue with their practice of eating human flesh, at one stage attempting to stop it but being rebuffed by the men asking if he would stop eating goat in return.

The Manyema were insubordinate to Barttelot in the first instance, leaving him to divide the rear column into two groups, leaving Jameson to bring up the rear with the second. On July 19, 1888, Barttelot was shot dead at Unaria. According to fellow officer John Rose Troup, Barttelot had ‘an intense hatred of anything in the shape of a black man.’ It transpired that the man who had killed Barttelot was named Sanga, and had done so in response to Barttelot’s threat (using a revolver) towards his wife. Barttelot wanted to stop the practice of singing and drumming early in the morning and in the evening. For his refusal of tolerance toward the Manyema porters, the Major paid the ultimate price, as other officers had likened him to ‘a fiend’ towards the Manyema, in correspondence to Stanley.

Jameson had no option but to rush forward onto Stanley Falls, where he was present at the trial and execution of Sanga, Barttelot’s killer. Only Tippu-Tib seemed able to control the unruly natives, and Jameson, therefore, obtained a promise for him to accompany the expedition. Before continuing onwards, Jameson had to obtain permission from the Emin committee in England, as the wealthy heir had offered to pay £20,000 of his own money that the expedition not be abandoned!

On his travels back to Bangala to make communication with home, a chill contracted by Jameson turned into hæmaturic fever by August 10. By the 17th, Jameson was dead, buried on the 18th on an island opposite the village. Jameson’s menagerie of expedition birds and insects were returned to his widow by 1890, with some particular specimens donated to the Natural History Museum in Kensington.

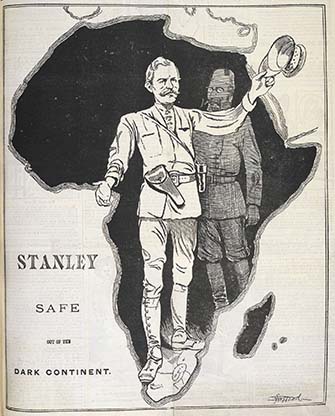

No relief for Henry Morton Stanley.

Morton Stanley was initially hailed as a hero on his return from the expedition, despite having presided over one of the worst organized expeditions in the Victorian Age. Despite Stanley’s bestselling new book, over time, the truth came out. Stanley was lampooned in repeated articles from The Times of London, and other newspapers, detailing the chaos that consumed the rear column.

The great man, the explorer who found David Livingstone, was embarrassed by the families of Barttelot and Jameson in particular – Samuel Baker describing the story as “the most horrible and indecent exposure that I have ever heard of seen in print.” Yet despite this, the world reeled at the actions of Jameson – contributing to the expedition being the last of its type, the explorers tainting their profession’s good name.

The next time a bottle of Jameson’s famous whiskey comes to your lips, remember the name of James S. Jameson, the sheep who, in the heat of Africa, strayed from his herd.