Almost 3,000 years ago, the ancient community of Teppe Hasanlu met a tragic end, pillaged and burned by unknown attackers. It left behind one of archaeology’s most poignant riddles: two human skeletons lying side by side in a plaster bin, locked forever in a loving embrace while the city around them was razed to the ground. These skeletons have been labeled the Hasanlu Lovers, for their eternal kiss; recently, however, that name was called into question, when it was confirmed that both skeletons were male.

Read on to explore the true story of the Hasanlu Lovers, and the ancient city they once inhabited.

The rise and fall of Hasanlu

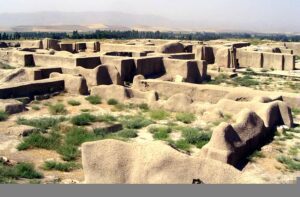

The Teppe Hasanlu archaeological site is located in the Naqadeh region, in the Iranian province of West Azerbaijan. Excavations show that this modestly sized city, surrounding a small mound, was occupied continuously from the sixth millennium BCE to about 800 BCE, when it was completely destroyed. It seems to have been attacked by invaders who slaughtered the inhabitants in the streets and set the settlement on fire. This complete and utter destruction marked the end of human habitation in the area, preserving the city’s ruins as a snapshot in time, not unlike Pompeii after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Archaeologists and historians do not know who attacked Hasanlu. They speculate that it may have been the Urartians, an Iron Age kingdom based in what is now Armenia, but the surviving evidence reveals little about the invading force.

Scholars are also unsure who exactly the Hasanlu people were. Diet analysis suggests that they ate wheat and barley, and artifacts around the site seem to indicate cultural ties with neighboring Assyria. We know almost nothing about how they identified themselves or what language they spoke. They seem to have had no system of writing. Beyond their grisly fate, the people of Hasanlu are a mystery.

Uncovering Teppe Hasanlu

Excavations of the Hasanlu site began in 1934 when the private British archaeologist Sir Aurel Stein bought the rights to investigate the area. He made a name for himself unearthing some of the most exciting archaeological finds in the area, including the Taklamakan oasis in the Chinese desert, and the abandoned city of Khara-Khoto in Mongolia. At Hasanlu, however, his work was only superficial.

Serious excavations began in 1956 with the initiation of the Hasanlu Project, a partnership between the University of Pennsylvania, the Metropolitan Museum, and the Archaeological Service of Iraq. Robert H. Dyson, from the University of Pennsylvania, led excavations there until the project’s conclusion in 1974. Archaeological discoveries and rare historical photos from the site would later be put on display at the Penn Museum.

Human remains found at Hasanlu

The remains of more than 285 people were unearthed at Hasanlu. The vast majority of skeletons seem to have been slaughtered in the streets by whoever invaded the city. They show head lacerations and dismembered limbs, and there is evidence of devastating fires all around the site—thousands of years later, the sheer violence of the attack comes through vividly.

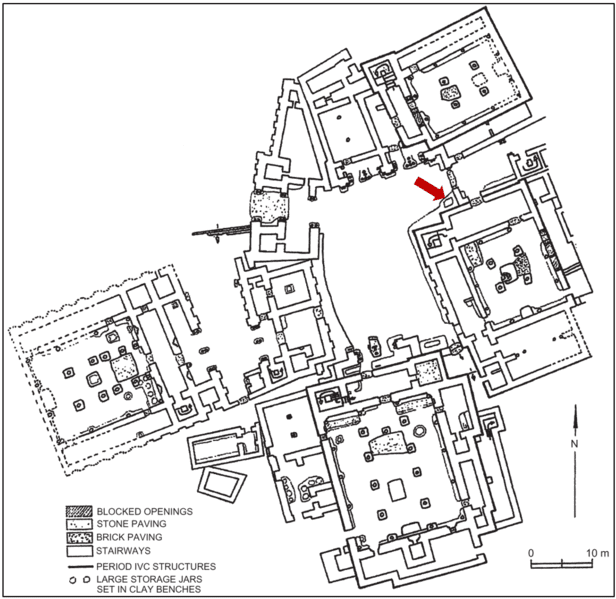

Two skeletons stand out: the Hasanlu Lovers. The pair were found in 1973, near the end of excavations. They were sealed in a plaster-lined brick bin, lying down one beside the other, with nothing else in the bin except for a stone slab under the head of one of the skeletons.

The skeleton on the right (known as HAS 73-5-799, or SK 335) is lying on its back, and seems to have its head turned towards the skeleton lying on its left. Its arm reaches around the back of the other skeleton, seemingly embracing it close.

The skeleton on the left (HAS 73-5-800, or SK 336), which has the stone slab under its head, is lying on its side, facing the skeleton on the right. One hand reaches up and touches the other’s face, and the two seem to be sharing a kiss.

Cause of death

There is nothing to indicate that they suffered the same trauma as their fellows in the street. Both appear almost fully intact. While one has a hole in its skull, the damage seems to have been inflicted by a pick during excavations. By all indications, they were quite healthy, with no sign of serious illness or injury during their short lives. So what were they doing in the bin? We will probably never know for sure, but it is believed they may have climbed in of their own accord, hoping to hide from the invaders ransacking their city. The absence of physical injuries suggests asphyxiation as a cause of death.

Lovers, or something else?

When excavators first discovered the skeletons, they assumed that they were looking at a young adult male and a female—an interpretation that was no doubt influenced by the heterosexual norms of 1970s. This attracted some attention from the media and public, who were drawn to the sensational idea of two lovers dying in each other’s arms. Examination of the skeletons’ physical characteristics soon complicated that narrative, however.

The skeleton on the right, SK 335, was identified as male early on, largely based on the shape of its pelvis. Its age was estimated at around 19-22 years. The skeleton on the left side, on the other hand, turned out to be more dubious. The pelvis has what anthropologists call a mixed morphology, meaning that it is difficult to determine whether the skeleton is male or female, but the cranium is distinctly male. While some scientists identified the skeleton as a slightly older probable male (30-35 years old), others continued to identify this skeleton as female.

Some mysteries solved

DNA testing to determine basic biological outlines was carried out on the remains starting in 2015 by the Anthropology Department of the Penn Museum and the University of Pennsylvania. This settled two key questions: it confirmed the suspected ages of the skeletons, and also confirmed that both of them were male.

Legacy of the Hasanlu Lovers

Considering that the Hasanlu Lovers come from a conservative region of the world, the confirmation of their sex has caused some controversy. Elsewhere, the discovery has been used to highlight that gender and sexual norms are socially constructed, and may not have been the same across cultures and throughout history.

Since we know so little about the Hasanlu Lovers and the culture they lived in, it is difficult to speculate what the skeletons represent. It is possible that the pair really were lovers, or that the kiss was a moment of solidarity as their world was destroyed around them. Ultimately, we cannot know what relationship these two people had. There is only so much we can glean from the tender embrace of the two skeletons, and in studying history, we must avoid projecting our present-day assumptions onto the distant past. The story of the Hasanlu Lovers remains as mysterious as it is tragic.