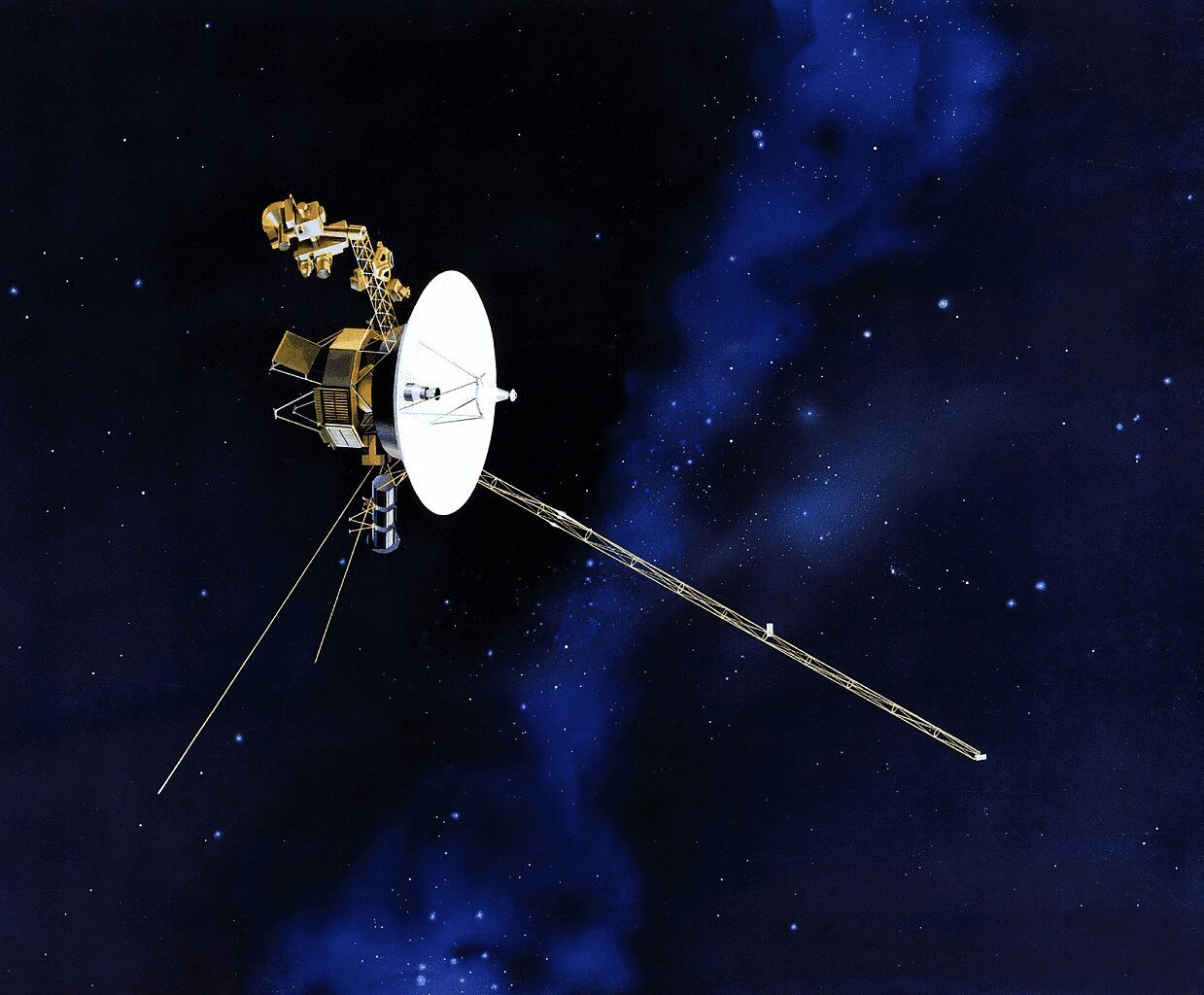

In all of human history, only five objects have left our solar system. All of them are NASA space probes: Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Voyager 1, Voyager 2, and most recently, New Horizons. They are our emissaries to the outer gulfs, destined never to return to the light of our Sun. Indeed, their slow drift will take them to places we can’t even imagine—and it is possible that somewhere out there, in the distant future, our robotic spacecraft will fall into the hands of intelligent beings like ourselves. What will they learn about us? What impression will they get from our wayward machines? In the late 1970s, the designers of the two Voyager probes asked those very same questions, and their answer was to launch into deep space a message for alien eyes: the Voyager Golden Record.

From pioneer plaques to the Golden Record

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were not the first spacecraft to achieve interstellar travel. That honor goes to the pair of Pioneer probes, launched in 1972 and 1973, to explore the then-uncharted outer planets. Pioneer 10 flew by Jupiter, while Pioneer 11 visited both Jupiter and Saturn, and both of them picked up so much speed during their planetary encounters that they were no longer bound by the gravity of the Sun—they were at escape velocity, headed into the wider cosmos.

This represented an unprecedented scientific opportunity. It also had a more profound implication: humanity was stepping out of the Solar System for the first time, and there was a real chance, albeit remote, that someone would eventually stumble across our probes. How could we put our best foot forward?

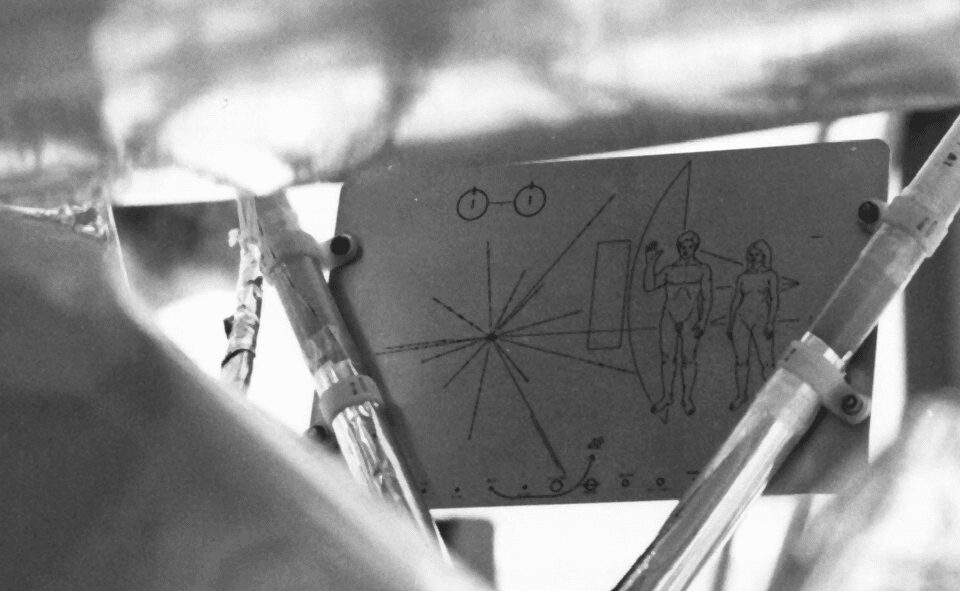

Astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake took on this challenge, designing a pair of metal plaques that would accompany Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 into deep space. Their job was to communicate with unknown beings, across the largest possible language barrier, hopefully getting across some basic facts about the human race. It turned out to be no small feat.

The chief problem was that an alien civilization would not use any known languages, nor would it understand human units such as meters and seconds. There wasn’t even a guarantee that they would count in base ten. Without any common frame of reference, Sagan and Drake had to get creative. As a basis for a universally intelligible system of measurement, they settled on a fundamental physical process that any spacefaring civilization would be familiar with: the release of electromagnetic radiation by a hydrogen atom. Such radiation always has a specific wavelength and period, providing units for both distance and time.

The final design was a plaque nine inches wide and six tall (22.9 by 15.2 cm), made from aluminum with a layer of gold for durability. Its most prominent feature was an illustration of a naked man and woman, standing side by side in front of the Pioneer spacecraft. To the left was a diagram showing the Solar System, as well as Earth’s position relative to various pulsars—with all values expressed in the universal units of hydrogen radiation. Ideally, an alien species could read that chart, and get some idea of where the probe came from.

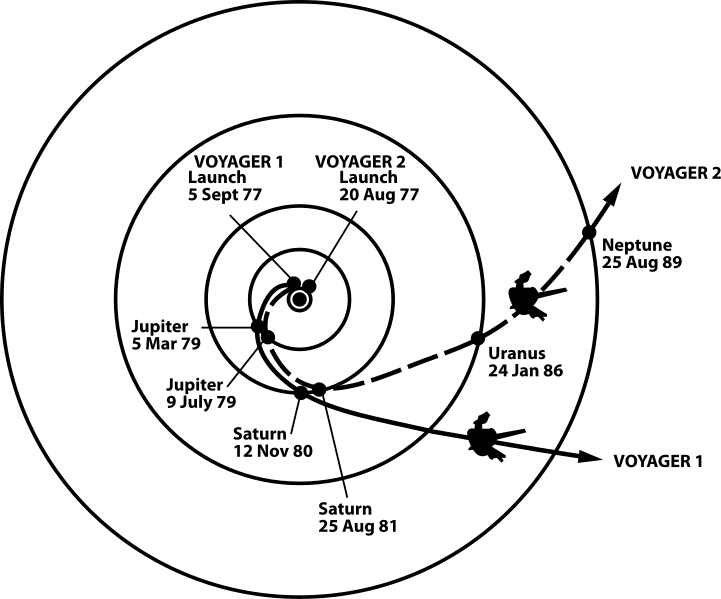

The Pioneer Plaques remain in deep space to this day. As groundbreaking as they were, however, they were limited in function. They conveyed a few basic facts about humanity, but not its soul. Surely a more sophisticated device could encode a wider swath of the human experience? When NASA launched the Voyager probes in 1977, bound for flybys of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune on their way to interstellar space, there was an opportunity to do just that.

Designing the Golden Record

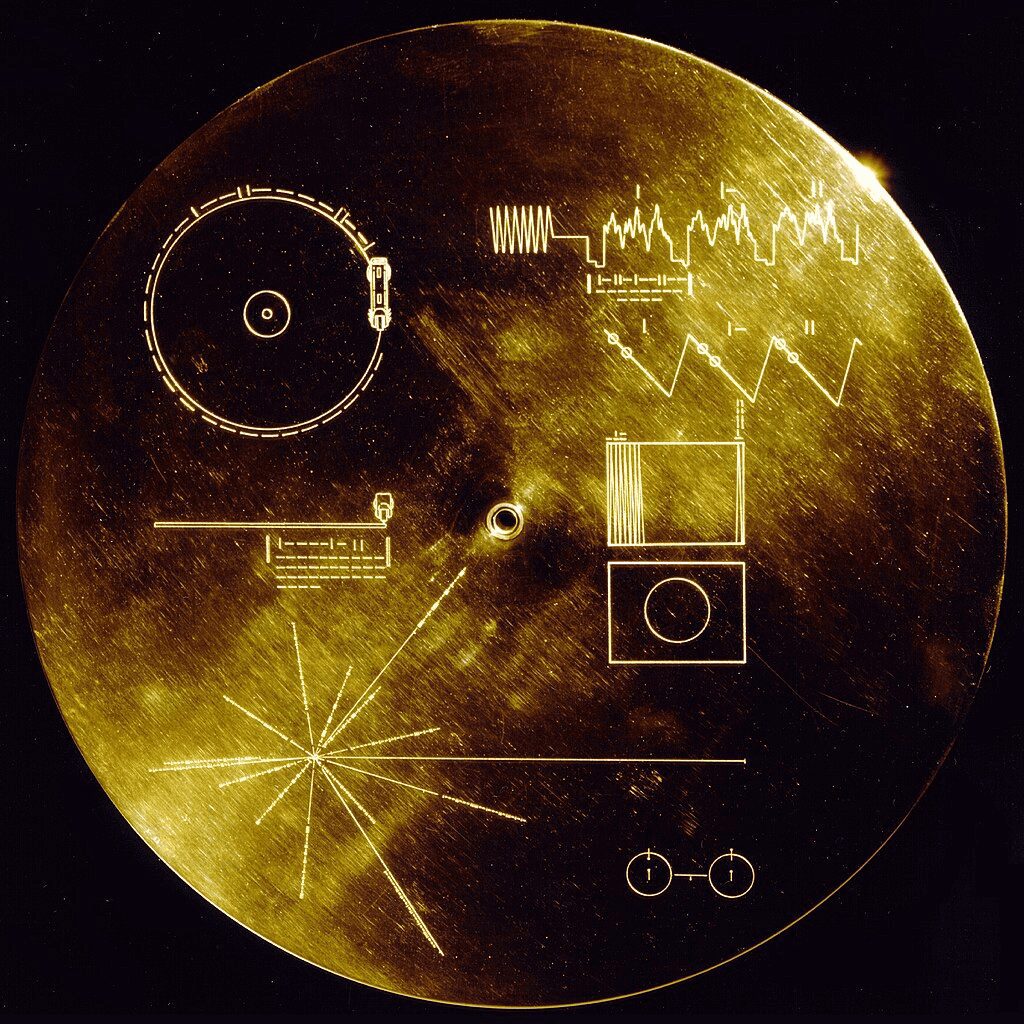

Thanks to his leading role in devising the Pioneer Plaques, Carl Sagan was appointed to helm the design of two phonograph records for the Voyager spacecraft, alongside Frank Drake, author Ann Druyan, and Sagan’s wife at the time, Linda Salzman Sagan. The choice of records for such a mission may seem strange at first glance; you would not expect to find an old-school vinyl hurtling through interstellar space, as opposed to a more “advanced” device. But this approach had its advantages. As a simple, bare-bones method of analog storage, it had no need for electric power or maintenance. It was remarkably compact, encoding a wealth of audio and images within a 12-inch (30-cm) disk. It was an enormous step up from the metal engravings that had gone out with the Pioneers.

A major challenge was that the Voyager spacecraft would face a never-ending barrage of radiation and micrometeorites as they drifted through the final frontier. As a result, the Voyager Golden Records had to be built for the long haul. Each record was made from gold-plated copper, with an aluminum casing to ward off space dust. Their engraved faces were pointed inwards towards the ship for additional protection. According to recent estimates, they are expected to hold up well—a 2022 study estimated that the records might remain legible for a mind-boggling five billion years.

The record cover

The Golden Record would be of little use if its recipients could not figure out how to interpret it. Sagan’s team couldn’t just assume that an alien species would know how to mount the record and construct its simple mechanical grooves into images and sounds; therefore, they added a diagram to the aluminum record cover, showing how to play the record, and how to translate its data line-by-line into something intelligible.

The design was the brainchild of Jon Lomberg, a longtime associate of Sagan’s. Playback instructions took up most of the space on the cover. Two other elements were reused from the Pioneer Plaques: a pulsar map, and an illustration of atomic hydrogen as a unit of measurement. The record’s cover also included a sample of uranium-238, with a half-life of 4.5 billion years. By analyzing the radioactive decay of the sample, which occurs at a predictable rate, a civilization could determine the approximate length of time since the probe launched from Earth.

The sights of earth

Sagan and his colleagues selected 115 images to accompany the Voyager probes on their journey. None were particularly high-resolution—they couldn’t be, encoded with only 512 lines each—but they were meant to provide a cross-section of human life and knowledge, capturing the world as it existed in the 1970s. Some were mundane; one image was of a woman snacking on grapes in a grocery store, while another showed children in a classroom. Other photographs covered important aspects of human civilization, such as the United Nations headquarters and the Olympic Games.

A similar variety of images showcased humanity’s scientific development: depictions of vertebrate evolution, a snapshot of the planet Jupiter, and a diagram of orbital motion from Isaac Newton’s Principia, to name a few. Black-and-white drawings laid out the basics of human biology and reproduction.

Unlike the Pioneer Plaque, in which every symbol was carefully selected for comprehensibility to alien minds, the Voyager Golden Record presented a wide assortment of pictures as-is. Would the recipients of this message be able to understand all of it? Of course not. Just from the contents of the record, they would never be able to figure out, say, what the United Nations is, or decipher the text on the page from Principia. But it would get them thinking. They would at least see what humans look like, and glimpse the world we live in.

The sounds of earth

After the 115 hand-curated images, the rest of the Voyager Golden Record was reserved for audio, formatted much like a music record for domestic consumption. Science journalist Timothy Ferris served as producer. As with the collection of photographs, the goal was to create the most representative possible cross-section of the human experience. There are 55 spoken greetings in different human languages, from English to Hindi to ancient Akkadian; 12 minutes of natural sounds of Earth, such as waves, flowing streams, and thunderstorms; and 90 minutes of music, combining an assortment of cultures and styles from around the world. Carl Sagan’s own son, six-year-old Nick Sagan, made an enthusiastic contribution: “Hello from the children of Planet Earth!”

The musical selection included songs as diverse as Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” and a Navajo night chant. Some themes got more attention than others—there were two compositions by Beethoven, and three by Bach. While this squeezed out other options, Ferris hoped that the mathematical structure of classical music would be of use to an alien species. Other global contributions included a wedding song sung by a young girl from Huancavelica, Peru, and a traditional Australian Aboriginal folk song, Barnumbirr (Morning Star). There was even a recording of the brainwaves of Sagan’s collaborator Ann Druyan; the hope was that an advanced civilization might be able to read her brainwaves, and peer into the inner workings of the human mind.

Into the great beyond

At the time of writing, Voyager 1 is 14.8 billion miles (23.9 billion km) from Earth. Voyager 2 is only a little closer in, at 12.4 billion miles (19.9 billion kilometers). That’s far enough for their signals to take nearly a day to reach Earth. Both probes have by now entered interstellar space, passing beyond the point where the solar wind is counteracted by particles from other stars.

That’s not to say that they’re heading anywhere fast, however. It will take tens of thousands of years for the Voyagers to reach any other stars, and even then they will pass at a few light-years’ distance. Looking further out into deep time, the picture isn’t much better—the probes will be slow, tiny, cold, and quiet, making them incredibly difficult for anyone to detect.

Nevertheless, each golden Voyager record is a time capsule in space. A message in a bottle, addressed to any other beings who might be sailing this vast, empty ocean, but also a portrait of a species entering its prime. What if that is the true value of the Golden Records, even if nobody ever finds them? Long after life on Earth has gone extinct, they will still be out there, preserving human faces and human voices, announcing to the universe: we were here!