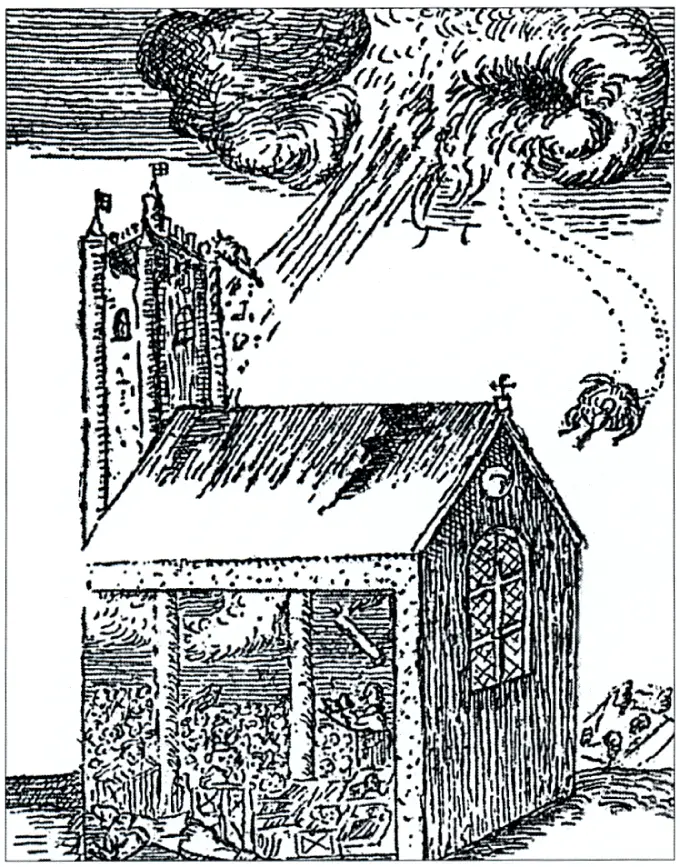

It was Sunday afternoon, October 21, 1638, and the church of St Pancras in the village of Widecombe-in-the-Moor, Devonshire, England, was packed with 300 expectant congregants. The vicar entered the pulpit, and the sky became cloudy and dark. But he never got the chance to deliver his sermon in this ominous setting.

Lightning flashed, and bizarrely, it was followed by a ball of lightning that struck the building. Unlike most ball lightning incidents, this one had tragic consequences. The ball ripped part of the roof off and rebounded through the building. Four people were killed, and sixty others were injured that day, some with severe burn wounds.

This event was so significant that it became one of the earliest documented accounts of ball lightning to date. Of course, a colorful local legend emerged, but the unmasked truth is that balls of lightning do fall from the sky and that most scientists now embrace this mysterious phenomenon.

When ball lightning appears

Statistical investigations indicate that up to 5% of the world’s population has seen ball lightning. That’s roughly the same amount as the people that have seen a lightning strike up close. There are thousands of accounts of ball lightning throughout history, as far back as the early Greeks.

There is even an account in one of Laura Ingalls Wilders’ semi-autobiographical “Little House” books set in the late 19th century. Laura describes how three balls of fire came down the metal stovepipe and were attracted to her mother’s knitting needles.

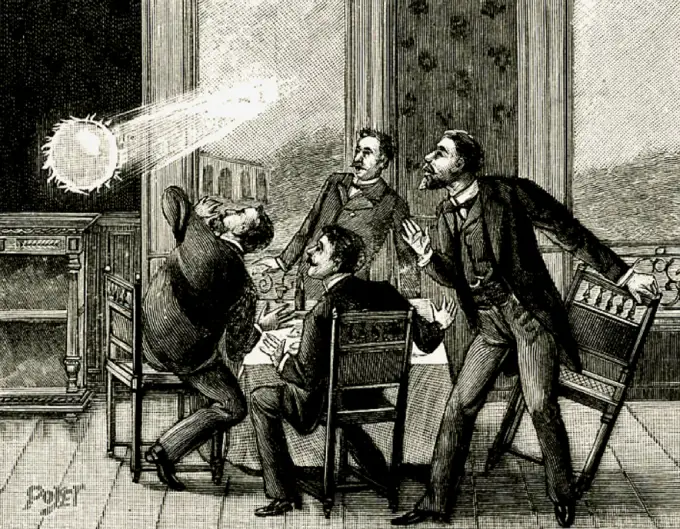

If you think older sightings lack credibility, there are plenty of reliable modern-day sightings with multiple witnesses to make you a believer. One German account describes ball lightning entering through an attic window and exploding spectacularly, even leaving marks on the laminate floor. Reports of ball lightning in aircraft also abound. They tend to enter through the front of the plane and move down towards the back.

Putting all the accounts together

Thanks to A.I. Grigoriev, who undertook an analysis of 10,000 ball lightning sightings, we know the general characteristics of most ball lightning.

Ball lightning is usually associated with a lightning strike, but not always. People typically see small spheres between the size of a grapefruit and a bowling ball (up to about 10 inches or 25 cm in diameter). The balls come in different colors: white, orange, blue, and very rarely, green.

Witnesses describe a luminous sphere with a floating motion. The balls hover above the ground, and sometimes they describe seeing the balls descend from the clouds.

The duration of ball lightning could be a few seconds up to several minutes—but the average time is usually about 10-25 seconds. The orbs can disappear with a spectacular bang or no bang at all. Witnesses often describe smells such as burning sulfur, nitrogen oxides, and ozone being left behind.

Indoor vs. outdoor ball lightning

Ball lightning can enter buildings through closed windows, thin nonmetal walls, and chimneys. While ball lightning has been reported to hurt and even kill people outdoors, indoor ball lightning is usually not associated with injuries. Unlike indoor cases, outdoor ball lightning also tends to end with a violent explosion.

Any plausible scientific explanation of what ball lightning is and how it works should be able to explain these general ball lightning properties, especially its floating motion, lifespan, and sudden disappearance.

Looking for the lucky lightning strike

To date, nobody is sure why this bizarre phenomenon occurs and how to explain it scientifically. Scientists are all the more frustrated because the high points they use to attract ordinary lightning seem never to attract any ball lightning. As Peter Handel, a ball lightning researcher, says: “It visits the farmer and avoids the scientist.”

So far, only a group of Chinese scientists have managed to observe, record, and determine the composition of ball lightning, and they did so only by a stroke of sheer luck while watching a thunderstorm. When they returned to the lab and ran their analyses, they found that the orb they observed contained the same elements as Earth’s soil: silicon, iron, and calcium.

Plasma clouds similar to ball lightning have also been created in a lab. Other than this, ball lightning research remains without solid evidence, leaving scientists floundering about for theories.

The dilemma: how to explain ball lightning

And those theories abound. Explanations using nuclear energy, electrical fields, vaporized soil, light, giant masers, and heat, to mention but a few, have been proposed over the last century. Karl Stephen from Texas State University explains the current state of affairs aptly: “There are literally dozens of ball lightning theories because it’s an unconstrained situation. Since there [are] virtually no data, anybody can come up with a theory, and you can’t prove them wrong.”

A few noteworthy theories explain what ball lightning consists of and how it comes into being, and they are all equally fascinating.

The light bubble theory

In a new paper by Vladimir Torchigin from the Russian Academy of Sciences, he describes how a bubble of light surrounded by a thin layer of compressed air particles could form ball lightning. The general idea is that there are many photons, such as light, spilling over after lightning strikes.

Because of the energy carried by the photons, the air absorbs and emits electromagnetic radiation, which causes small forces that move air particles around. Though these forces are minuscule, a lightning bolt is intense enough to magnify them when a thin air bubble forms. This bubble would be able to concentrate the photons into a ball of rotating light that has an intensity a billion times greater than light that travels in a straight path. Since the bubble is made of light, that easily explains how it enters buildings through windows.

Torchigan has thoroughly and elegantly crunched the numbers and states in the paper that “the question of the nature of ball lightning [is] resolved.” However, the theory neglects to explain the composition of ball lightning as measured by the Chinese spectrograph. Why have silicon, iron, and calcium been detected if the spheres are made of light?

The hot soil theory

John Abrahamson and James Dinniss from the University of Canterbury came up with a plausible and simple theory, published in Nature in 2000. According to this theory, a shockwave of air particles from a lightning bolt can result in hot ionized silica (from the soil) that turns into silica nanoparticles. As the particles are oxidized slowly in the air, they release energy in the form of heat and light. Astonishingly, this paper was published twelve years before the lucky Chinese researchers found silicon in ball lightning.

The ions-on-either-side-of-the-window theory

John Lowke from the CSIRO in Australia doesn’t believe that the silica theory could explain how lightning goes through closed windows. Lowke has been tinkering away at ball lightning theories since the 1960s, and time hasn’t dissuaded him.

In his latest theory, Lowke and his colleagues propose that columns of charged air particles, several miles in length, are produced from lightning bolts—sort of like a stepped ladder. The ions pile up outside a window on one side. This makes ions of the opposite charge accumulate inside the window, leaving a ball of plasma to move around inside the building or plane. This imaginative theory might explain why ball lightning inside buildings behaves differently from how it does outside.

The way forward

So – which is it? A theory with all the physics of electromagnetic radiation and the numbers of light density and the air pressure required to back it up? Or is it the theory backed by the only existing scientific evidence – where silica particles create light and heat? Or is it the one that explains how these ghostly orbs enter buildings so well?

Before you place any bets, hold your horses. Martin Uman, the world’s leading lightning scientist, says that “there are probably multiple causes for what’s described as ball lightning.” In other words, maybe they are all right!

Karl Stephen and Richard Sonnenfeld take a unique approach to the ball lightning problem to tease out fact from fiction. Since scientific evidence is elusive, they are exploring eyewitness accounts in a much more rigorous fashion than ever before by harnessing the power of citizen science. They’ve invited people to detail their ball lightning sightings. With modern technology at their fingertips, they hope to compare the sightings with weather radar systems to determine what factors breed the perfect ball lightning storm.

Ball lightning could have a simple explanation that can be understood with current physical laws. Or, it may turn our current understanding of physics entirely on its head. For now, though, ball lightning remains a specter that will haunt physicists until the reasons are discovered.