France is a sporting nation, but football has always held center stage and a favored status. There is, however, a blemish on this country’s football history that many would rather forget, and that is the infamy of Alexandre Villaplane.

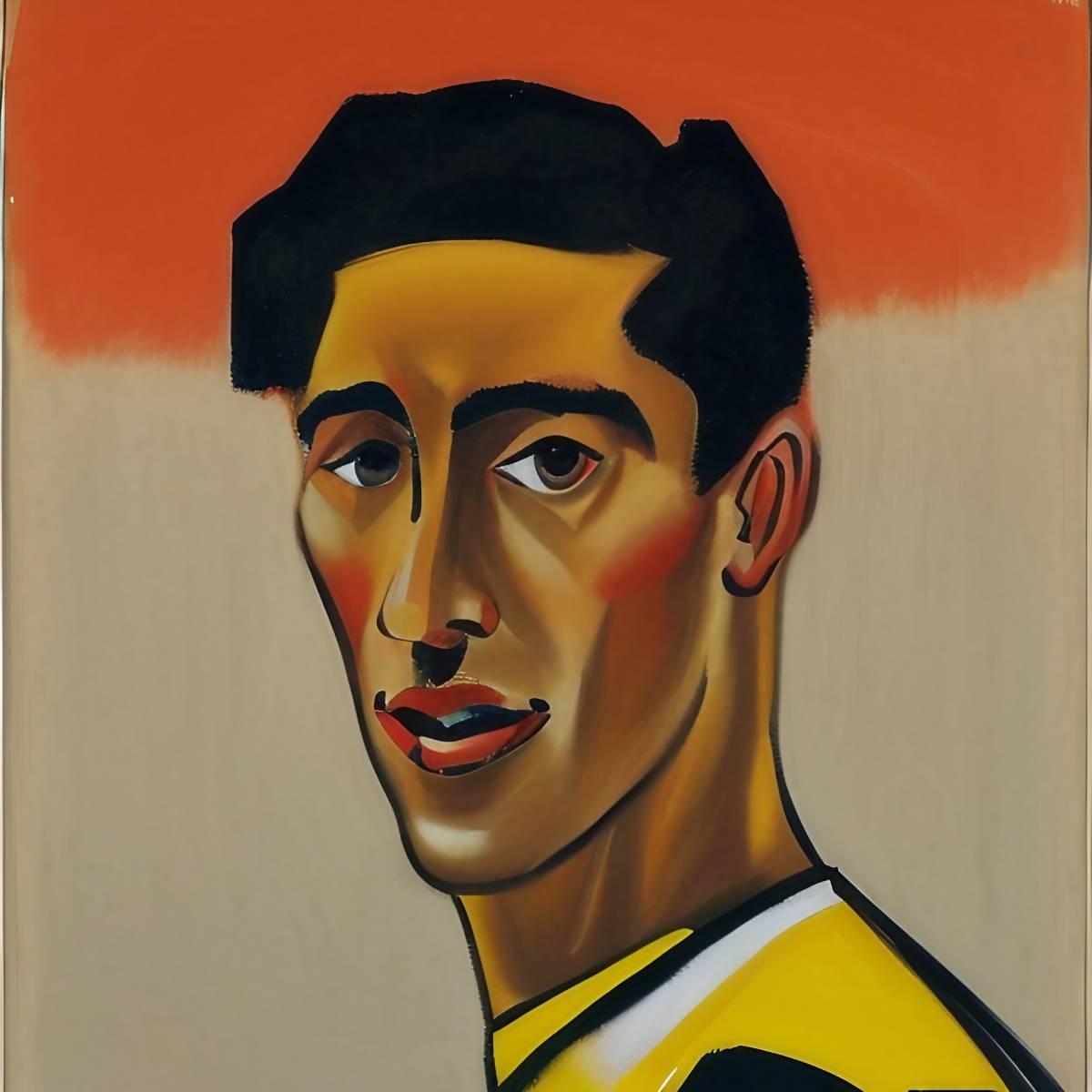

Villaplane was the outstanding French center-half before the Second World War and the first footballer of North African descent to represent and captain the French national team. However, during World War II, his betrayal and murderous behavior ensured a villainous legacy far removed from feats of footballing glory.

Alexandre Villaplane’s life in Algiers

Alexandre Villaplane was born in Algiers in 1905 in French Algeria.

For native Algerians, life in colonial Algeria was tough and precarious. The French pacification of Algeria lasted from 1835 until 1903. French Colonel Lucien de Montagnac stated the objective of pacification was to “destroy everything that will not crawl beneath our feet like dogs.” The brutal scorched earth policy that accompanied pacification was devastating in its success. Political scientist Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison estimates a third of the population was killed during this period.

Growing up, Villaplane experienced extreme poverty. Some would later wonder if this was the reason behind the obsession with wealth that would dominate his behavior in later years. Indeed, the specter of brutal French colonial justice would still be fresh in the memory of his family.

At the age of sixteen, Villaplane left Algeria to go to mainland France where he took up residence with his uncle on the south coast. Villaplane’s move was a common migration route for impoverished North African immigrants. However, the mainland population did not always welcome arrivals from colonial North Africa with open arms. Animosity towards the ‘pieds-noirs‘ and the teenager’s almost total lack of formal education meant that his life would have been challenging.

A glimmer of hope

There was one ray of hope for Villaplane. He was a gifted footballer; the beautiful game offered an escape from the drudgery of poverty, which appeared inevitable.

Spotted by talent scouts from local club FC Sète in 1921, Villaplane’s potential was nurtured by Sete’s English manager Victor Gibson. Gibson was an interesting character. Born Arthur Henry Gibson in Woolwich, England, he joined Espanyol in 1911 after touring Spain with Plumstead FC. A year later, he would join Olympique Cettois (later becoming FC Sète), beginning a twelve-year association as player-manager. Gibson’s Sète side lost in the 1923 and 1924 French Cup Finals. However, Gibson would reverse his luck by managing a Marseille side that achieved French Cup success in 1926 and 1927. Likewise, after Victor Gibson departed, FC Sète would enter football history by becoming the first French side to secure a league and cup double in 1934.

Under Gibson’s tutelage, Villaplane soon established a reputation as an aggressive and hard-tackling player. This would have been a dream come true for many, but Villaplane had grander ambitions and began looking for opportunities that could elicit greater financial rewards.

The rise of shamateurism

The development of sporting tradition was especially strong in academic institutions during the 19th century. Educational establishments were almost exclusively attended by the upper and middle classes who could afford entrance fees and had the luxury of time to pursue sports. Social change was ushered in in the UK by the Factory Act of 1850. All work would end at 2 pm on a Saturday, presenting an opportunity for the working classes to participate in sport, albeit limited.

The obstacles facing the working class in sports were also political. The elite controlled the sporting establishment, who preferred certain sports to retain an amateur status. It was simply unacceptable that the working man competed successfully in top sporting competitions previously dominated by the middle and ruling classes. Regardless, teams developed popular concepts such as ‘broken time payments’ with players paid to take time off work.

Pre-1932, the official amateur status of football in France was no deterrent to ambitious clubs seeking glory. Clubs could easily circumvent financial rules and amateur status by offering bogus employment with bumper salaries.

Villaplane would embrace shamatuerism and the money that came as a result.

Aged 18, Villaplane seized on this new opportunity. In a move that surprised everyone, he dropped to a lower division by signing for Entente Perrier Vergèze in 1923. The club situated just 70km from Sète had wealthy backers, the Perrier mineral water company, which had the money to offer Villaplane a deal he could not resist. The uncompromising center-half returned to FC Sète after one season, presumably on more favorable terms, and remained with his hometown club until 1927.

Captaining France at the inaugural World Cup

He would first represent France against Belgium in 1926, and Villaplane would quickly cement his place in the Les Bleus squad. Further plaudits followed, representing France at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics. However, the undoubted highlight of his international career was when he captained France in a 4-1 victory against Mexico at the inaugural World Cup in 1930. He won twenty-six caps and led France on three of those occasions. When Villaplane debuted as Captain, he told the press that it was ‘the happiest day of his life.’ That feeling of contentment was soon to pass.

In France, being Captain of the national football team places you just a few rungs below God in the public’s perceived pecking order and several rungs above the President. What happened next for France’s sporting national hero was unexpected.

Villaplane’s international playing career came to an abrupt and baffling end when he was 24 years old, in a 3-2 defeat against Brazil, shortly after the 1930 World Cup. His ability was undoubted, so why was one of the finest players of his generation ostracized from the national team?

In pursuit of greater rewards

In 1927 Alex Villaplane left FC Sete to join the wealthier and more prestigious Sporting Club Nîmois (reformed as Nîmes Olympique in 1937.) The money and public adoration attached to this team meant Villaplane was becoming a household name, and his future looked bright.

However, 1927 also saw Villaplane blighted by injury. His absence from the national team was particularly noticeable. It was no coincidence that Les Bleus missed their hard-tackling talisman in a year when they experienced multiple humiliating defeats, culminating with a historic 13-1 loss against Hungary.

Many would have thought that Villaplane had reached the pinnacle of his ambitions. After all, he was the son of impoverished working class immigrants, poorly educated and of North African origin. Nothing could be further from the truth. He was well paid, wanted more, and viewed football as a gateway to a lavish lifestyle.

Racing Club de Paris

1928 saw Villaplane appearing seven times for the national team. Despite below-par international results, Racing Club Paris poached him from Sporting Club Nîmois in 1929. The President of the Parisian club, Jean-Bernard Levy, was determined to usurp the success of city rivals Red Star. Levy saw the talented Villaplane as a vital piece of the jigsaw that would make Racing club de Paris the most prestigious club in French league football.

Villaplane was well-paid, but it still predated the start of the French professional championship, when even greater sums of money would enter the sport.

Parisian underworld

Alexandre Villaplane was still in his twenties and now a national celebrity; he began to frequent clubs, bars, casinos, and horse racing tracks. He soon fell in with unsavory elements of the French underworld and various gang members. His association with Parisian gangsters cultivated a personal network that would influence the outcome of the rest of his life. Ultimately his behavior off the field and links to Parisian gangsters spelled the end of his international career. The enfant terrible of French football was now considered ill-suited for selection by the footballing bureaucracy. Villaplane would never play for his country again after returning from the 1930 World Cup.

French professional championship

The French Football Federation voted in favor of professionalism during a 1930 vote (128 for 20 against). Despite this, it would be another two years before the establishment of the National Championship. The twenty-club league had various stipulations that member clubs had to observe. One of these rules was that clubs had eight professional players on their books.

Match fixing scandal

It would be two years before the French authority’s decision to exclude Villaplane from the national team was vindicated. 1932 introduced a new league format in concert with professionalism. Villaplane returned to the South of France lured by big-spending minnows FC Antibes.

Villaplane’s side excelled and surprised many by winning the Southern Section of the league championship. However, the season finished in controversy. An investigation was conducted after a five-nil away victory for FC Antibes against SC Fives Lille. FC Antibes was found guilty of bribery and match-fixing and disqualified from the championship.

Valère, the club manager, received a lifetime ban. Villaplane was never formally charged with match-fixing crimes. Still, so much evidence pointed towards the participation of both himself and two other team members that FC Antibes decided to let him go.

Dropping standards

Villaplane found himself playing for OGC Nice in the first division. Les Aiglons desired an improvement on the seventh-place finish from the previous season. Villaplane was appointed team captain, but the relationship between club and player soured. Results were poor, and disciplinary issues surfaced with training sessions missed regularly. Relegation was inevitable, and Nice terminated their relationship with the former star.

His next move was to the far less prestigious second division team, Hispano Bastidienne de Bordeaux. Signed by his old mentor Victor Gibson, Villaplane had come full circle. But, again, unprofessional behavior let him down, ending a playing career that had once shown immense promise.

Horse race fixing scandal

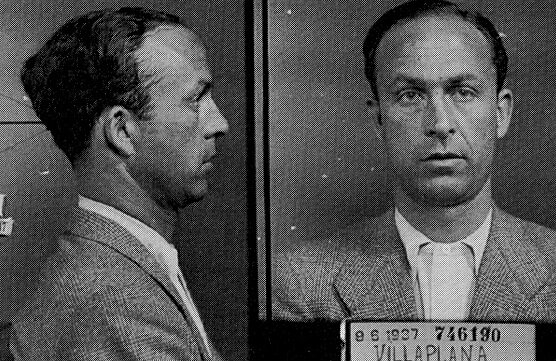

If he was concerned about this dramatic change in the direction his life was taking, Alex Villaplane didn’t show it, and it wasn’t long before he was rubbing shoulders with gang members from the underworld. In 1934 he was sent to prison for a horse race fixing scandal.

The Nazi invasion

For a man who had once been a national legend, it looked like Villaplane’s life was destined to continue its downward spiral towards anonymity. In 1940 the Nazi invasion of France changed everything. The course of world history altered forever, and Villaplane made choices that would bring about his downfall in spectacular fashion.

Henri Lafont

He teamed up with Henri Lafont, who he probably already knew well through dealings with the criminal underworld. Lafont was a lifelong criminal. Henri was born in 1902; his real name was Henri Chamberlin. Chamberlin’s father died when he was eleven years old, claiming his mother abandoned him at the graveside. He frequented reform institutions and prisons and even escaped from a penal colony as a boy.

Lafont took one look at what was happening with the Gestapo invasion and decided that it posed a massive opportunity to those ruthless enough to seize it. He was one of the first collaborators to offer his service to the occupying Nazis.

At first, even the Germans were wary of doing business with a man of such ill repute. Still, they set him an almost impossible task of tracking down and capturing a Belgian intelligence asset named Lambrecht. Lafont finally caught up with Lambrecht in the free zone and then smuggled him back to Paris bound hand and foot in the trunk of a car. Interrogation followed, resulting in the collapse of the Belgian counterintelligence service and the arrest of 600 agents in the network.

The French Gestapo

Lafont had established his usefulness, and the Nazis began using him for many malicious tasks. Soon Lafont was amassing a fortune by running a series of different rackets under the guise of destroying the Paris black market. He surrounded himself with a gang of thugs and henchmen, many of North African origin. He then daringly proposed to the Nazis that they be amalgamated into a military unit which was to be named the Brigade Nord Africain. Villaplane was awarded the rank of SS Sublieutenant in the new brigade.

Although the brigade’s role remained ambiguous, they were essentially in place to do the dirty work that the Nazis preferred to distance themselves from. They became adept at interrogation and did not stop using techniques such as pulling out nails and burning with blow torches and the ice bath to gather information. In hunting down Jews and members of the resistance, they could add to their wealth by stealing any property they managed to get their hands on.

We will probably never know quite how much they managed to acquire, but we do know that to curry favor with one deputy of the secret police, Helmut Knochen, Lafont offered the man a Bentley.

Brigade Nord Africain to Perigueux

By 1944, the tides were beginning to turn against the Nazi invaders. The resistance in the Perigord region was becoming a real headache for Hitler and his forces. He dispatched the Nord Africain Brigade to the area with orders to destroy all resistance activity. Villaplane played a prominent role in this operation, and it is believed that he never shied from using some of the brutal techniques for which the brigade was so feared.

In June of that year, members of several resistance fighter groups gathered at a town called Mussidan in the Dordogne department, where they intended to blow up a bridge. When the explosives never arrived, they attacked a troop train instead, and several combatants from both sides were killed.

The Mussidan massacre

The 11th German Panzer Division responded to the attack, and on arrival at Mussidan, they rounded up all men between the ages of sixteen and sixty that they could get their hands on. In total, they took 350 hostages before calling in the Brigade Nord Africain to do the interrogation. Known locally as the ‘bicots,’ Villaplane was an active member of the interrogation team. They selected fifty-two of the hostages and gunned them down in a ditch on the outskirts of the town. It is alleged that at least ten victims died at Villaprane’s hand.

The event was one of the most notorious in the west of France during World War II, and the village was subsequently awarded the Crois de Gere. The atrocity is still commemorated on an annual basis in France.

An attempt to build alliances

This war crime and many others committed at the time indicated a Nazi army in disarray. And even to Villaplane, it was becoming increasingly apparent that things would not turn in the Nazi’s favor, and he was about to find himself associated with a hated regime. He tried to gather some degree of support by releasing some of the Resistance fighters he captured in the hope they might support him at a later stage.

Execution

His efforts were in vain, however. In August of 1944, Paris was liberated, and it was only a matter of time before the French Gestapo were rounded up and made to stand trial. On Boxing Day of the same year, Alexandre Villaplane and Henri Lafont were executed by firing squad at Fort de Montrouge outside Paris.

Wealth over humanity and patriotism

Today, it is not uncommon to see famous football stars crash and burn as they struggle to deal with the heady heights of stardom. Few, however, have done so quite as spectacularly as Alexandre Villaplane managed to. There have been many that have speculated on the reasons for his demise. Some suggest that a childhood of poverty caused his greed to blind him to his success. Others reason that he must have been wholly depraved and had no moral conscience to do what he did. The truth is, we will never really know. What is certain is that this is one football hero who the French would rather forget.