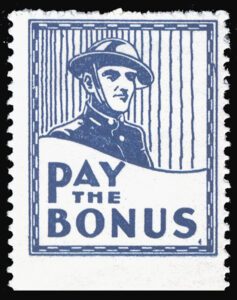

“Patriotism, bought and paid for, is not patriotism,” US President Calvin Coolidge said on May 15, 1924, after vetoing a bill granting bonuses to returning World War I veterans. Just four days later, Congress overrode the veto, enacting the World War Adjusted Compensation Act, better known as the Bonus Act.

Under the Bonus Act, the veterans were supposed to receive “Adjusted Service Certificates,” which worked pretty much like insurance policies and could be redeemed for cash in 1945, at the end of a 20-year maturity period. But then, in 1929, the Great Depression began, and by 1932 more than half a million of the World War I veterans remained unemployed.

Desperate for money and a way to put food on the table, some of them demanded early payment of their bonuses. The government was reluctant to comply, fearing that an early payout would make it hard to convince future generations of soldiers to fight. But the vets were adamant, and in 1932 they converged on Washington, D.C., in what became known as the “Bonus Army” protests—one of the most dramatic and disgraceful episodes in American political history.

Veterans benefits: a brief history

Veterans’ benefits have existed since time immemorial. Ancient Egyptians and Babylonians, as well as Greeks and Romans, they all had various reward systems for military service beyond daily pay. Sometimes this was simply “sharing the plunders” of war in overseas service, but most commonly, it was granting the rights to some newly conquered land.

The Greeks were the first to introduce benefits for the extended family of a soldier. Centuries later, the Crusaders and other chivalric orders were the first to set up hospitals specialized for injured veterans. By the 17th and the 18th century, monarchies all around the world used similar incentives and land grants to attract and retain loyalties. The British, of course, were no exception.

As a result, by the time of the Revolutionary War, American colonies had already inherited a strong tradition of basic veterans’ benefits and pensions. However, World War I saw an unprecedented number of Americans in military uniform. Fearing that immediate payments for their services could lead to inflation and put an unnecessary burden on the already-stretched public purse, the government created a long-term plan to pay benefits over time, aka the Bonus Act.

Unfortunately for everybody, inflation paid a visit either way, storming through a backdoor: the stock market crash of 1929, and the ensuing Great Depression.

The costs of being a World War I veteran

By the time the Great Depression had begun, the vast majority of World War I veterans had already been quite exhausted by 14 years of foot-dragging by the federal government in dealing with their immediate issues. The Great War had changed so much, and not for the better. Most pressingly, it forced many of the returning American soldiers who had served overseas into abject poverty and hopelessness—and even homelessness!

There are, after all, clear opportunity costs in being a soldier, going beyond risking your life to fight for your country. Debilitating injuries aside, all those World War I veterans had missed business and career opportunities in the name of their governments. They were separated from their loved ones and their network of friends and associates for many months, and sometimes even years. Last but not least, many of them had come back psychologically damaged, carrying all kinds of traumas caused by mustard gassing, shell shocks, enemy captures and/or living in sordid and squalid trenches.

For millennia, granting land and some part of the war plunder to a veteran could solve some of these issues. But not in the 20th century: cities had gotten overpopulated, jobs could become obsolete overnight. World War I demonstrated that, in addition to regular pay during active duty and a deserved pension afterward, returning soldiers needed a few things more, such as say work-life and job assistance. Otherwise, many of them couldn’t reintegrate into society and civilian life. Indeed, while some returning veterans found their ways back into decent lives, others ended up losing everything: their jobs, their spouses, their homes.

What was the Bonus Army?

For many World War I veterans, the Great Depression was the proverbial final nail in the coffin. While the financial crisis had made life worse for almost every American living in the 1930s, WWI veterans were hit especially hard, and not only those who hadn’t found a proper way to reintegrate into society and civilian life.

They felt that they had earned their bonuses justly—with blood, toil, tears and sweat—and they were getting more and more adamant that they couldn’t wait for their money anymore—and certainly not until 1945! An investment in the future is no investment at all if you die in the meantime.

So, in mid-1932, around 20,000 of these veterans and their families, led by WWI veteran Walter Waters, decided to demand their money then and there and marched on Washington. They dubbed themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.) as a nod to the American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.), a famous US Army formation on the WWI Western Front. However, they became much better known under their media moniker: the Bonus Army.

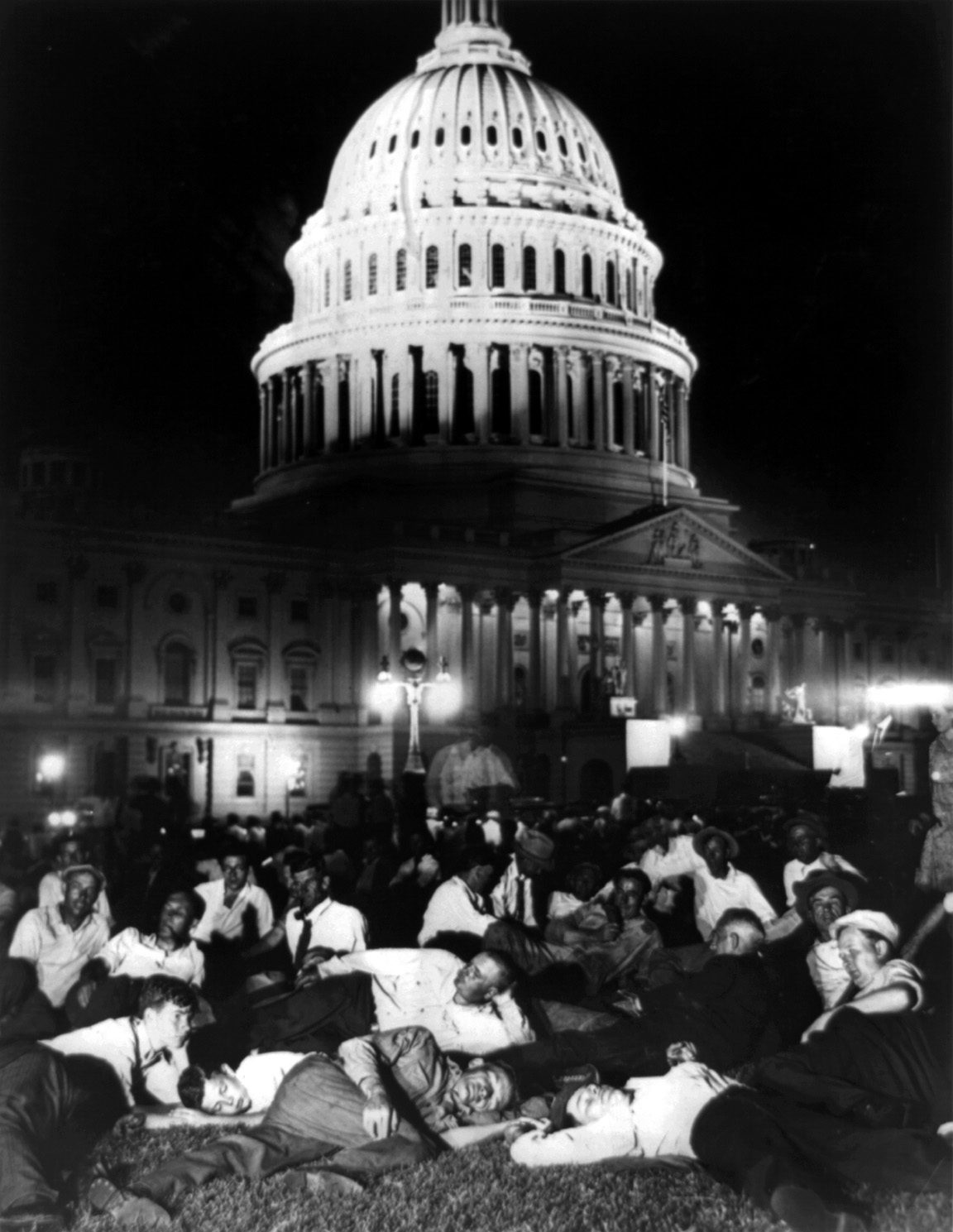

The Bonus Army camped out in abandoned buildings and quickly became a stark reminder of the effects of the Great Depression—and a very visible target for a government that wasn’t sure how to deal with them.

A different kind of Hooverville: the Bonus Army camp

Already in the spring of 1932, several encampments sprung up in the heart of the nation’s capital. The largest Bonus Army camp—which grew to include almost 20,000 people—was located along the Anacostia River, directly opposite the seats of power, the US House of Representatives and the Capitol.

Most of the campers were World War I veterans and their families, but they were also joined by some few hundred unemployed men from all over the country. They lived in tents, clapboard shanties, and makeshift camps; for some of the soldiers, it felt like a déjà vu all over, a sort of homecoming to the trenches. Except the enemy was now quite different—the very government they had fought for a decade and a half ago.

Unlike some other Hoovervilles and Hooverite slums, the Bonus Army camp was neither violent nor dirty. In fact, the campers were generally well-behaved and kept their camp clean, even building a sanitary system and enacting pest control. They did, however, make a point of protesting in Washington, D.C., and that drew the attention of the press and the administration of President Herbert Hoover.

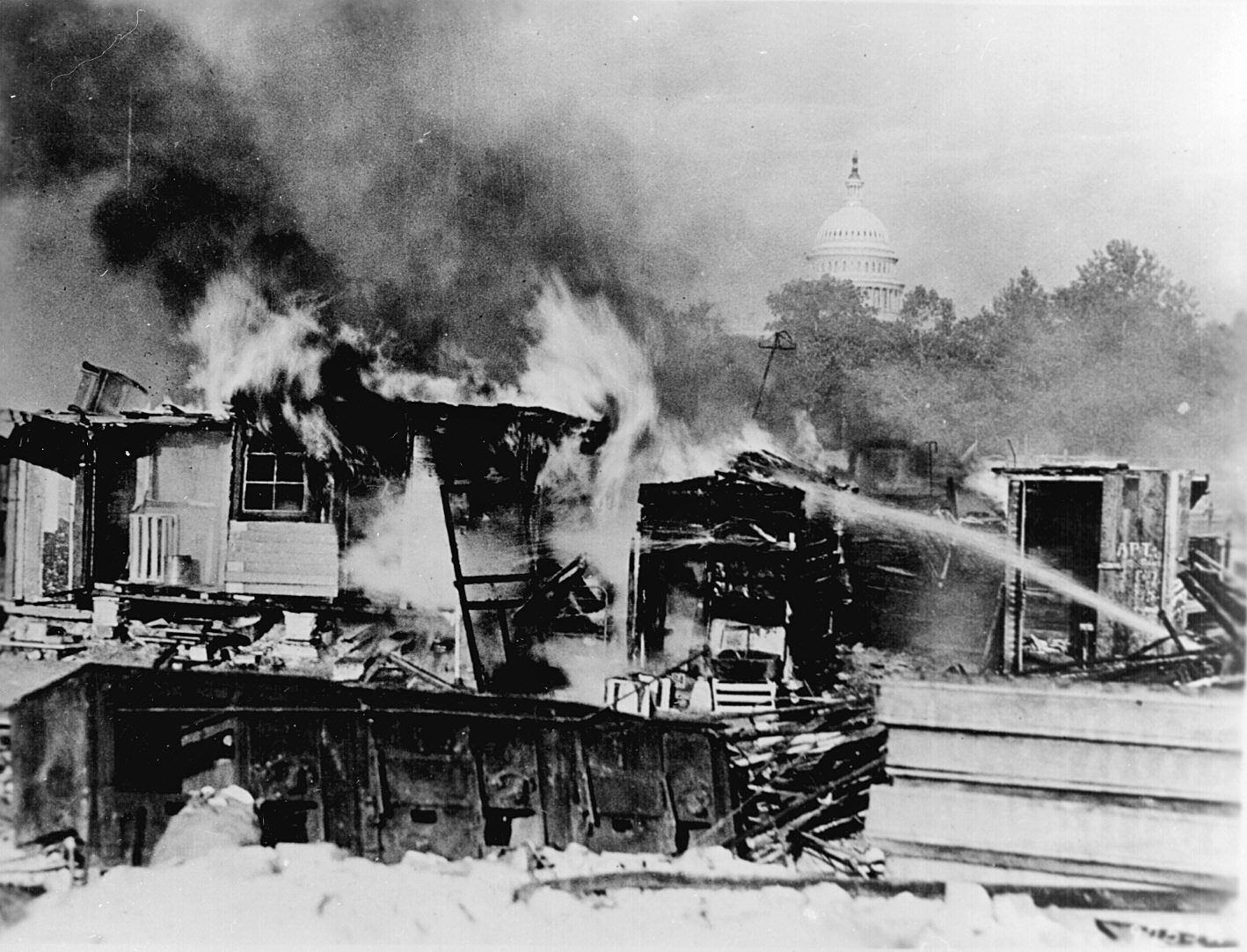

Having privately proclaimed his “distaste for the spectacle,” in July 1932, Hoover ordered the camp to be broken up and sent troops to force the Bonus Army to leave Washington. What followed was one of the most disgraceful episodes in American military history.

The Bonus Army march on Washington (and the bill that should have been)

A few weeks before Hoover decreed the veterans’ removal from Washington D.C.—more precisely, on June 15, 1932—the United States House of Representatives passed the so-called Wright Patman Bonus Bill to provide early payment of the veterans’ certificates. Despite building pressures, the Senate promptly rejected the Bonus Bill, with some senators citing the cost of the bill and others feeling the bonus had been an unnecessary handout in the first place.

It was the last straw. In the days that followed, thousands of campers left the campsites and headed toward the Capitol in what is today known as the Bonus march. Its goal is not clear to today. Some say the Bonus Army marchers were actually heading to protest the vote in a peaceful sit-down strike in front of the building. Others feel that they were heading down Pennsylvania Avenue and trying to reach the White House in a futile attempt to get the president on their side. Yet a third group claims that they were just spontaneously and planlessly voicing their disapproval of the Senate’s vote.

Either way, the Bonus marchers had now entered government property, thereby giving Hoover an opportunity to deal with them. And deal he did—in a most brutal, Soviet-like fashion that caused even the few remaining pro-Hoover newspapers and magazines to howl with outrage in the aftermath.

The Battle of Washington: World War II heroes vs World War I veterans

On July 28, 1932, under the instructions of President Hoover, US Attorney General William D. Mitchell ordered that the Bonus marchers be removed from all government premises. Two people died in the ensuing riots. Hoover used the riots as an excuse to order the US Army to forcefully clear the campsites as well. Later that night, highly equipped army troops and no less than six tanks, led by future World War II hero Maj. George Patton—and under the overall command of Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur—crossed the bridge over the Anacostia River. The die was cast.

Before too long, the shacks in the Anacostia Camp were aglow with fire. Tear gas flowed and machine guns were fired. As the cavalry charged, members of the infantry began clearing the makeshift tents one by one, using their bayonets with relish. According to witness accounts, they were completely indiscriminate in the endeavor, booting families with small children with pretty much the same force as they did men in fighting fitness.

One of these evicted men was Joe Angelo, recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross for his services in World War I. In 1919, General Patton had described him as “without doubt, the bravest man in the American Army.” He knew this from personal experience: on September 26, 1918, Angelo had saved Patton’s life after the general had been seriously wounded by a German machine gun. Even so, when Angelo approached his former leader in the midst of the Anacostia Camp assault, Patton told him off. “I do not know this man,” he is said to have told a nearby officer, his words dripping with contempt. “Take him away and under no circumstances permit him to return.”

In an attempt to avoid a public relations disaster, Hoover gave Gen. MacArthur an order to stop the assault. MacArthur, however, either didn’t get the message or chose to ignore the President’s command, believing these to be seditious protestors seeking to overthrow the government. Either way, his goal remained the same: to disperse them at any cost. It turned out to be quite a high cost in the end: 55 casualties, all of them on the Bonus Army side. Among the casualties were two veterans, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, and a 12-year-old boy named Bernard Myers who died in the hospital due to gas complications.

The aftermath: (not) taking responsibility

The highest cost of the Bonus Army incident was, arguably, one that could not be measured in numbers or unnecessary deaths, but in what the incident came to symbolize in its smoldering aftermath: the public loss of trust in the actions of the federal government. Among other things, the events of July 28, 1932, are widely considered to have been a major contributing factor to Hoover’s landslide loss to Franklin D. Roosevelt in the presidential elections of that year. Even so, the incident did nothing to derail the careers of the military officers involved.

The unflattering credit for this goes to future US president Dwight D. Eisenhower who served as one of Gen. MacArthur’s junior aides during the assault and was tasked with writing the official report. Despite private reservations, he publicly supported MacArthur’s version of the events. The violence inside the campsite, Eisenhower wrote, had escalated to a point where action needed to be taken. While it was wrong from the US army to attack fellow war veterans, it was far worse to let them march on and risk the overthrow of the democratically-elected US government.

However, neither the press nor the public were fully satisfied with the initial explanation. The veterans, understandably, even less. The mounting pressure paved the way for the Adjusted Compensation Payment Act in 1936, which overrode an earlier veto by President Roosevelt and authorized the immediate payment of the WWI rewards to the bonus seekers. The law set the groundwork for the final, triumphant, chapter of this sad story: the passing of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act in 1944, one of the most important pieces of American legislation of the twentieth century.