In a world of complex systems and intricate policymaking, it is easy to forget the power of even the smallest of our actions. Easier still is to disregard or pass over their potential unintended consequences. “The cobra effect,” a term coined by German economist Horst Siebert in the 1950s, is an illustrative example of this, and one that has long been used to caution those in positions of power and influence, responsible for designing and implementing policies.

In short, the cobra effect is a phenomenon in which an attempted solution to a problem actually makes the problem worse. In detail, it is a tale of shortsightedness and miscalculation, of blind optimism and naiveté, of good intentions gone terribly wrong. It is also, most importantly, a lesson in the significance of understanding the full implications of our decisions, no matter how trivial or well-meaning they might be.

The original cobra effect

The cobra effect got its name from an incident that supposedly occurred in British colonial India during the late 19th century.

Faced with an increasingly unmanageable problem of wild cobras roaming the streets of Delhi, the British colonial government began offering bounties for every dead cobra turned in by citizens. This looked like a reasonable solution—reward those who killed the snakes, and the problem would eventually be solved.

However, unbeknownst to the British, this seemingly well-meaning solution had an unexpected outcome. Seeing an opportunity to make a quick buck, many local citizens began to breed cobras for the specific purpose of collecting the bounty. The result? The wild cobra population remained largely unaffected, and the government was forced to scrap the bounty program and look for an alternative solution.

That didn’t make things better, though. Namely, when the bounties were canceled, all those home-bred cobras suddenly became worthless. So, the cobra breeders set them free, thereby making the original problem even worse than before the British government stepped in to solve it.

Goodhart’s law

The cobra effect earned its seductive name only recently, at the beginning of the new millennium, through Horst Siebert’s book of the same title, at least to our knowledge still untranslated into English. Even so, as a phenomenon, it had been observed and studied for quite longer than that, a few decades at the least.

In economics, for example, the cobra effect is still best known as Goodhart’s law, named after British economist Charles Goodhart. First formulated in 1975 as a critique of Margaret Thatcher’s monetary policy, Goodhart’s law suggests that any measure or indicator of economic performance that is used to inform a decision or policy will eventually fail if it is used as the basis for that specific decision or policy.

The reason is simple, if not even obvious. Namely, when we make a target out of a specific measurement and connect it to a reward, it creates a motivation for people to cheat the measurement in order to get the reward. In the succinct phrasing of anthropologist Marilyn Strathern, Goodhart’s law states that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” However, it’s quite likely that Goodhart wasn’t the first to realize this.

Campbell’s law

A few years before Goodhart formulated his law, American sociologist Donald T. Campbell described a similar pattern in the field of behavioral research.

Starting with his 1969 article on “Reforms as experiments,” Campbell argued, among other things, that the greater the number of individuals or groups that are affected by a policy or measure, the greater the likelihood that the measure or policy will be abused or misused.

Around the same time as Goodhart, in a widely quoted article, he formulated his original idea in a way which is now commonly referred to as the Campbell’s law:

The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.

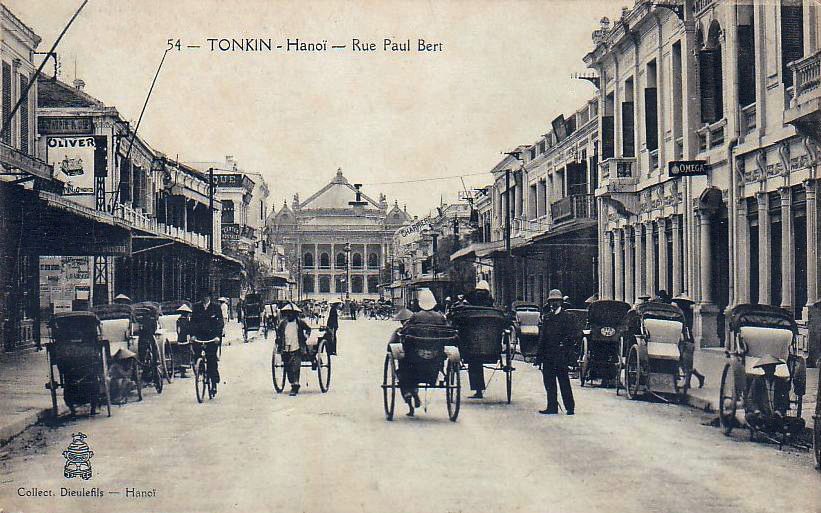

The Great Hanoi Rat Massacre of 1902

It can be argued, with American historian Michael G. Vann, that the most fitting name for the intriguing phenomenon of perverse incentives is neither the cobra effect, nor Goodhart’s or Campbell’s law. Indeed, the term “rat effect” might be more suitable than all three, as the scenario was first observed in the case of the Great Hanoi Rat Massacre.

The story begins in the late 19th century, when Hanoi—then under French colonial rule—was facing a serious rat infestation. The rats were causing damage to crops and spreading disease, so the government was under pressure to find a quick solution to the problem. When cases of the bubonic plague began to show up, they responded in force.

In the spring of 1902, hundreds of professional Vietnamese rat-catchers were sent by the French into the sewer systems of Hanoi. In the first few days, they only managed to kill a few hundred rats, but as they perfected their technique, the numbers quickly jumped into the thousands, culminating on June 12, when a staggering 20,114 rats were captured and killed in a single day!

And then, from June onward, the rodent corpse count began to dwindle. Dissatisfied with their wages, the rat-catchers expressed their frustration by killing fewer and fewer rats. Faced with a collective labor action and an ever-growing rat population, the French were pressured into finding an alternative solution. So, they decided to create a citywide bounty program.

“The best-laid schemes of mice and men…”

In the summer of 1902, the government authorities of French Indochina announced they would pay any citizen a bounty of 1 cent for every rat tail brought in as proof of a kill. It was determined, after some deliberation, that requiring the submission of an entire rat corpse would place too heavy of a load on the already stretched municipal health authorities. This seemingly smart decision proved to be quite fateful in the end.

It wasn’t long before Vietnamese residents began to bring in thousands of tails. It wasn’t long as well before local officials began to notice something far less assuring—tailless rats roaming around the city streets, nibbling away at whatever edible goods were left in their path. It quickly became apparent that the bounty program had backfired. The Vietnamese weren’t killing rats; they were just cutting off their tails, and releasing them back into the wild—to breed and produce even more valuable tails!

In the suburbs, health inspectors witnessed something even more disturbing. Namely, to their utter dismay, they found out that some of the poorest residents of Hanoi had begun raising rats and cutting off their tails—so as to collect the bounty! Rather than dealing with the Hanoi rat problem, the government was actually aggravating it. By the end of 1902, they had no choice but to abandon the rat bounty program, with the Hanoi infestation problem still as bad as ever, if not even worse.

Unintended consequences everywhere: three other examples of the cobra effect

India’s Cobra Campaign and the Great Hanoi Rat Massacre of Hanoi are prime examples of how positive feedback, in the form of a reward, can spiral out of control and lead to a negative outcome, eventually causing more harm than good. It is often said that “the road to hell is paved with good intentions,” and this certainly applies to these two famous cases.

Unfortunately, they aren’t just isolated instances, by any stretch of the imagination. On the contrary, many other examples of the cobra effect can be found all over the world. Here are just a few of them, randomly selected.

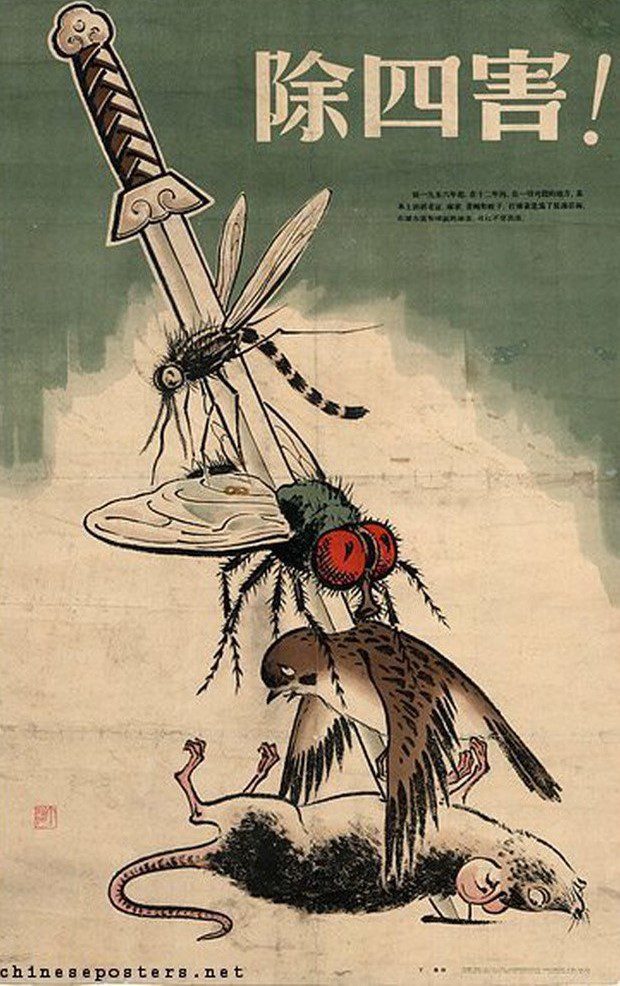

From sparrows to locusts: China’s misguided “Smash Sparrows” campaign

In an effort to increase grain production, in the late 1950s, the Chinese government launched the smash sparrows campaign, part of the Four Pests campaign. The campaign encouraged citizens to kill sparrows, as they were believed to be eating too much of the grain—at least 4 pounds (2 kg) of it per sparrow per year!

The campaign was so successful that the sparrow population of China was nearly eradicated by 1960. However, what the Chinese government didn’t account for was the unintended consequence of the decreased sparrow population—an increase in the number of locusts, which began to freely feed on the grain crops, causing far more damage than their predators ever could.

In due course, the Chinese government admitted its mistake and resorted to importing 250,000 sparrows from the Soviet Union to restore the lost ecological balance. By then, however, it was too little too late: the smash sparrow campaign led to an exacerbation of the Great Chinese Famine, which reportedly killed tens of millions of people.

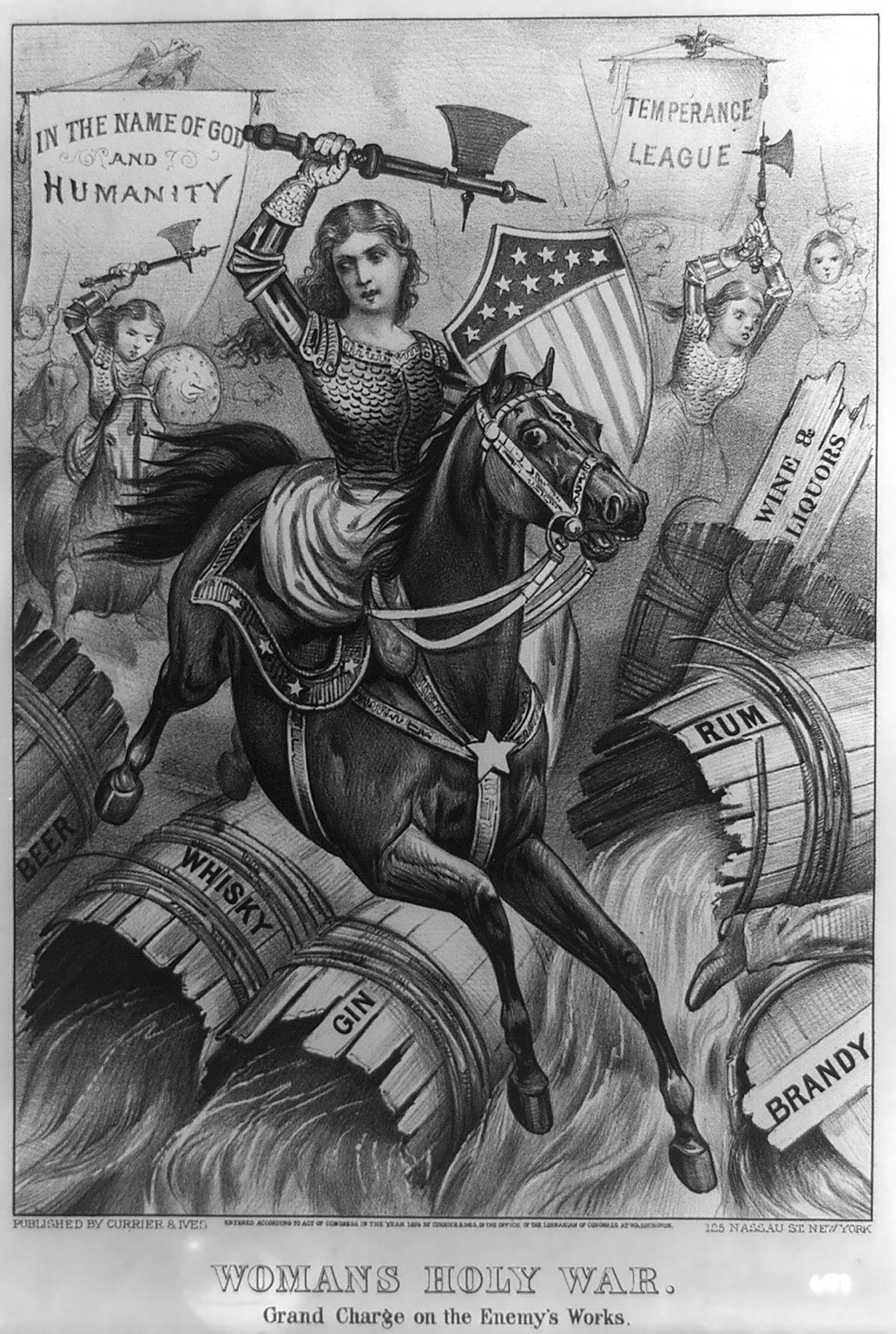

The United States and its failed attempts to solve crime

A few decades before Mao Zedong began reforming China, the United States government banned the sale, production, and transportation of alcohol, in a nationwide effort to reduce crime and improve public health.

The Prohibition Era—which lasted for thirteen years, from 1920 to 1933—was successful in reducing the consumption of alcohol and improving the health of American citizens, but ultimately it failed in achieving its primary goal of reducing deviant behaviors.

Instead, the ban led to an increase in organized crime as illegal alcohol production and sales became a profitable venture for criminal organizations. The rise of these criminal organizations led to an increase in crime and violence, particularly in urban areas.

A similar example is Nixon’s War on Drugs, which has been widely criticized for creating a feedback loop in which harsher penalties for drug offenses led to a higher incarceration rate, which in turn led to more poverty, crime, and ultimately—more drug offenses!

The Cobra Effect in Mexico City: how banning cars led to more cars

One more recent example of the cobra effect in action is a policy that was implemented in Mexico City in 1989, when the government introduced the Hoy no circula (“No driving today”) program which banned all drivers from using their vehicles one weekday per week, on a rotating basis.

In accordance with the regulation, cars with license plate numbers ending with 0 or 1 weren’t allowed to drive on Monday, those ending with 2 or 3 weren’t allowed to drive on Tuesday, and so on and so forth.

The program was intended to reduce pollution and traffic congestion in the city by limiting the number of cars on the road. However, it achieved pretty much the very opposite, as many residents chose to purchase a second car to use it on the days their primary vehicle was banned.

This ultimately led to an increase in car ownership and a failure to achieve the desired reduction in pollution and traffic congestion. Additionally, the program disproportionately affected low-income residents who could not afford a second car and were unable to get to work on the days their primary vehicle was banned.

In conclusion

In all of the above examples, the initial solution, while well-intentioned, created a feedback loop that ultimately worsened the problem rather than solving it. Hence, the cobra effect serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of understanding the complexities of feedback loops, and the potential consequences of our actions.

Moreover, it highlights the dangers of oversimplifying complex problems and taking a one-dimensional approach to problem-solving. In a complex world, any action can create a cascade of unintended consequences, so it’s essential to understand the dynamics of positive and negative feedback before taking any steps, lest we want to risk creating a situation that can spiral out of control.

Finally, the cobra effect also serves as a cautionary tale of the importance of transparency when creating policy. In many of the examples, the cobra effect could have been avoided had decision-makers been open to feedback from those affected by their policies, and had they considered input from experts in the field. Without such transparency, the cobra effect could all too easily be repeated.